18 West 86th Street

New York, NY 10024

Hours

Tuesday–Sunday: 11:00 am–5:00 pm

Thursday: 11:00 am–8:00 pm

Explore this interactive map to discover the relationship between the artworks on view in Waterweavers and seven rivers in Colombia (Amazon, Bogotá, Cahuinarí, Cauca, Magdalena, Putumayo, and Ranchería). It’s your choice to navigate using the points on the map, or to make selections from the “List of Artists” tab on the top right. The “Exhibition” tab activates the artworks in Waterweavers within the map; the “Images of the River” tab activates photographs of the rivers; and the “Map” menu allows users to select different map views.

In Colombia, a country whose complex topography has historically caused waterways to be the only means of transportation between many communities, rivers have both united and separated people. Today, when most of the population lives in cities, rivers continue to serve as the sole access to remote areas, but they also play a new role, as the axis for a different type of economics: the black market (in drugs, minerals, guns, money, and so on), which fuels the armed conflict that has plagued Colombia for decades. Waterweavers, the exhibition, considers these issues from very different points of view as it presents a territory laden with conflict while showing the creative output that nevertheless thrives in the midst of—or in response to—hardship. Using the the river as a conceptual device to explore the intersections in Colombian contemporary culture between design, craft, and art, Waterweavers investigates the intricate ways in which culture and nature can intertwine across disciplines. Drawing, ceramics, graphic design, furniture, textiles, video, and installations evoke a concept informed by social, political, and ecological strife in Colombia.

Please visit the BGC Website for further information about visiting the gallery, the exhibition catalog, and gallery programs.

Waterweavers was on view at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery from April 11–August 10, 2014. The exhibition was curated by José Roca with Alejandro Martín, and organized by the Bard Graduate Center Gallery. Unless otherwise noted, the text on this site is excerpted from Waterweavers: A Chronicle of Rivers, edited by José Roca and Alejandro Martín, and published by the Bard Graduate Center, New York City. All photographs are provided courtesy of the artists, unless otherwise credited in the image captions, and are protected by copyright. Interactive design by Alex Hills and Kate Dewitt, BGC. Funding for Waterweavers is generously provided by Vivian Haime Barg, Alberto Mugrabi, and Leon Tovar Gallery. In-kind support provided by Christie’s and Phillips. Special thanks also to Cristina Grajales Gallery.

18 West 86th Street

New York, NY 10024

Hours

Tuesday–Sunday: 11:00 am–5:00 pm

Thursday: 11:00 am–8:00 pm

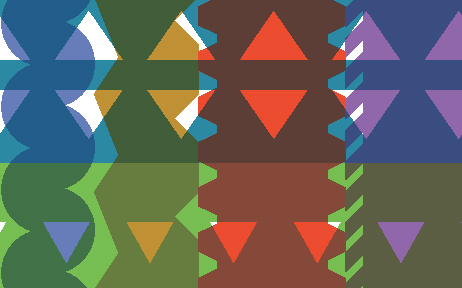

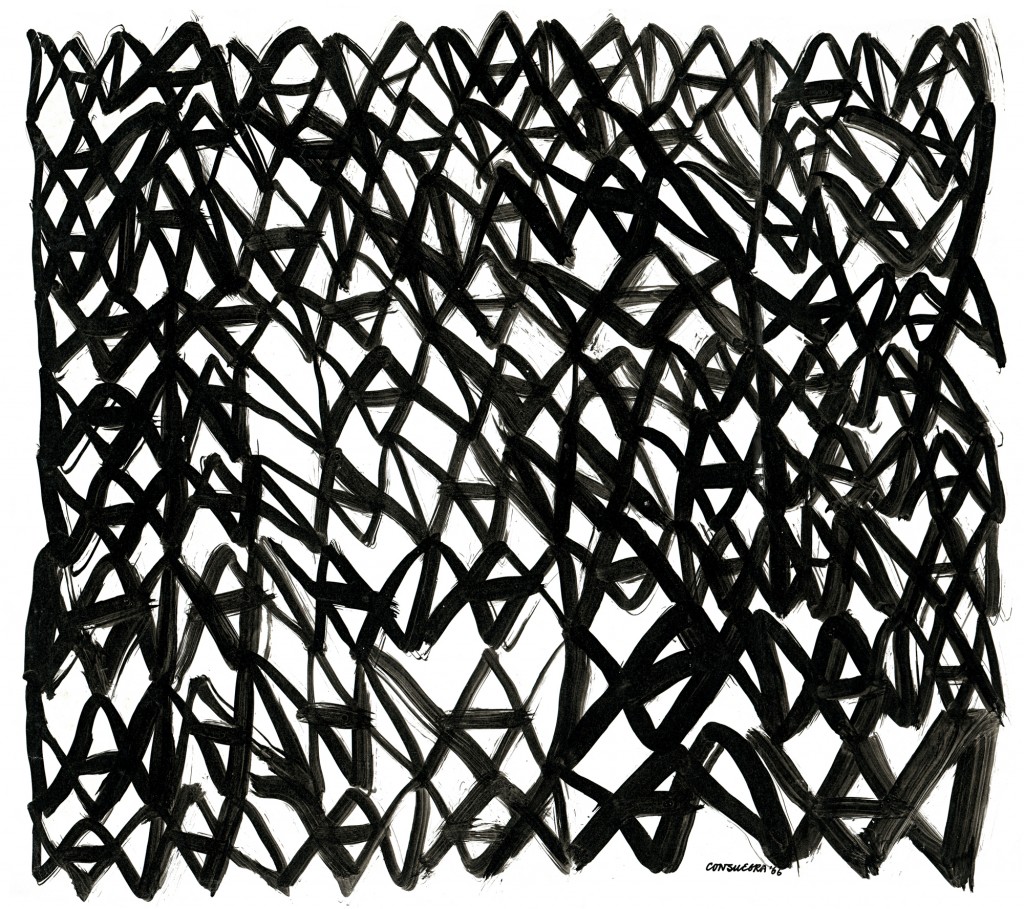

Tablet-optimized web application based on David Consuegra’s designs for Ornamentación calada en la orfebrería indígena precolombina (1968)

Interaction design and development by Thomas Hines

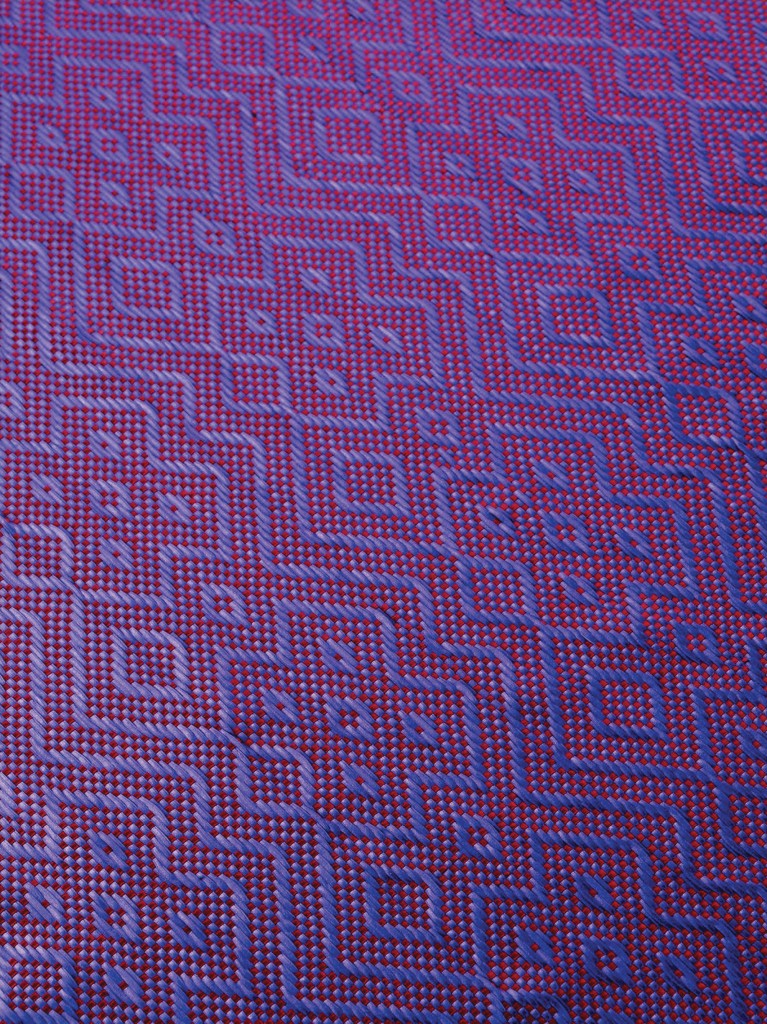

Given their conceptual interest in patterns and their demonstrated design talent, Tangrama was invited to participate in Waterweavers. They were given the challenge of revisiting and elaborating on the graphic elements David Consuegra identified in pre-Hispanic objects produced by the Muisca and Tolima cultures, as they appear in the book Ornamentación calada en la orfebrería indígena precolombina (Decorative Openwork in Pre-Columbian Indigenous Metalwork).

Inspired by themes of the river and of weaving, the members of Tangrama recognized that the pre-Hispanic patterns Consuegra identified could be reproduced in an infinite, linear fashion. For this exhibition they developed an interactive digital application that could set the patterns into virtually limitless motion, thus transforming each pattern into a river (water), while also allowing users to superimpose layer upon layer (weavers).

This project is analogous to what Consuegra achieved in his book. By extracting an element from each indigenous artwork, he demonstrated the graphic wealth of pre-Hispanic cultures. Similarly, by setting these elements into motion, and by triggering a virtually endless series of reproductions and superimpositions, Tangrama exposes the true potential of these graphic units as patterns. The project is as simple and powerful as the tangram game, in which the broken pieces of a square can generate a universe of forms solely through the art of combination.

View the application and make your own designs.View the application and make your own designs in the gallery.

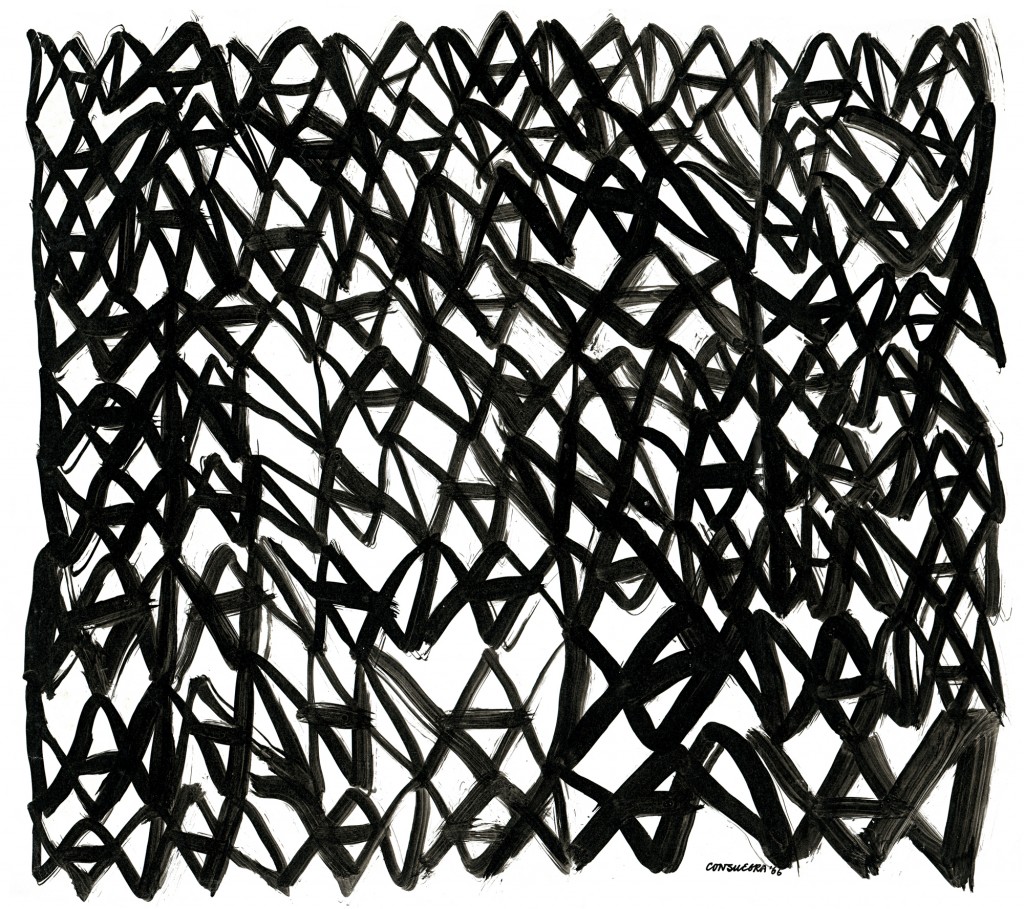

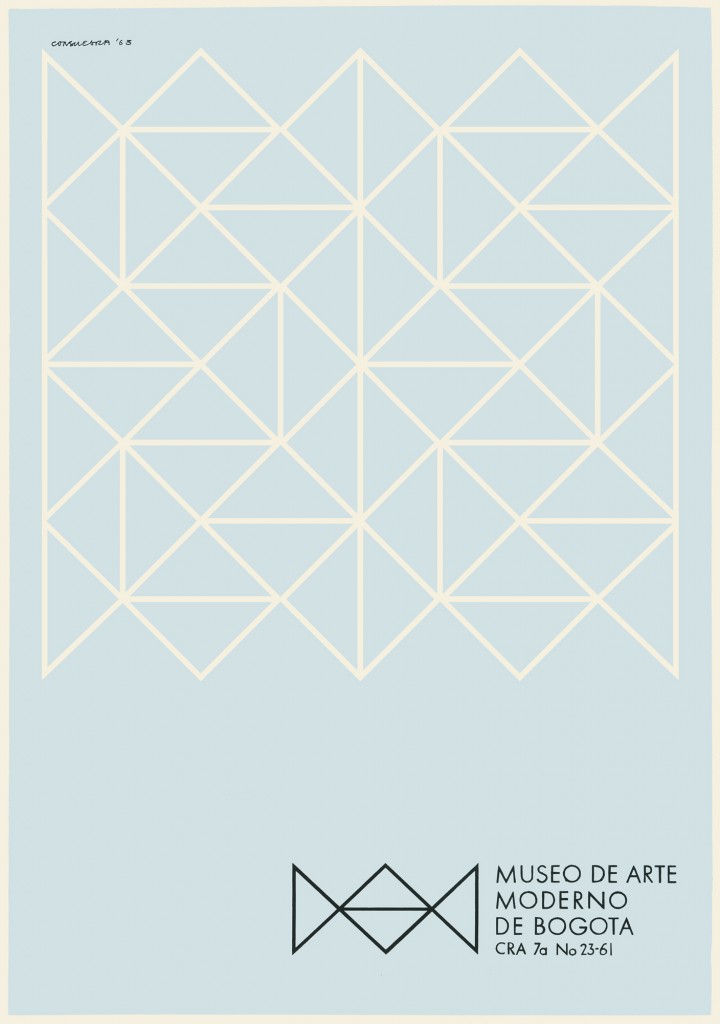

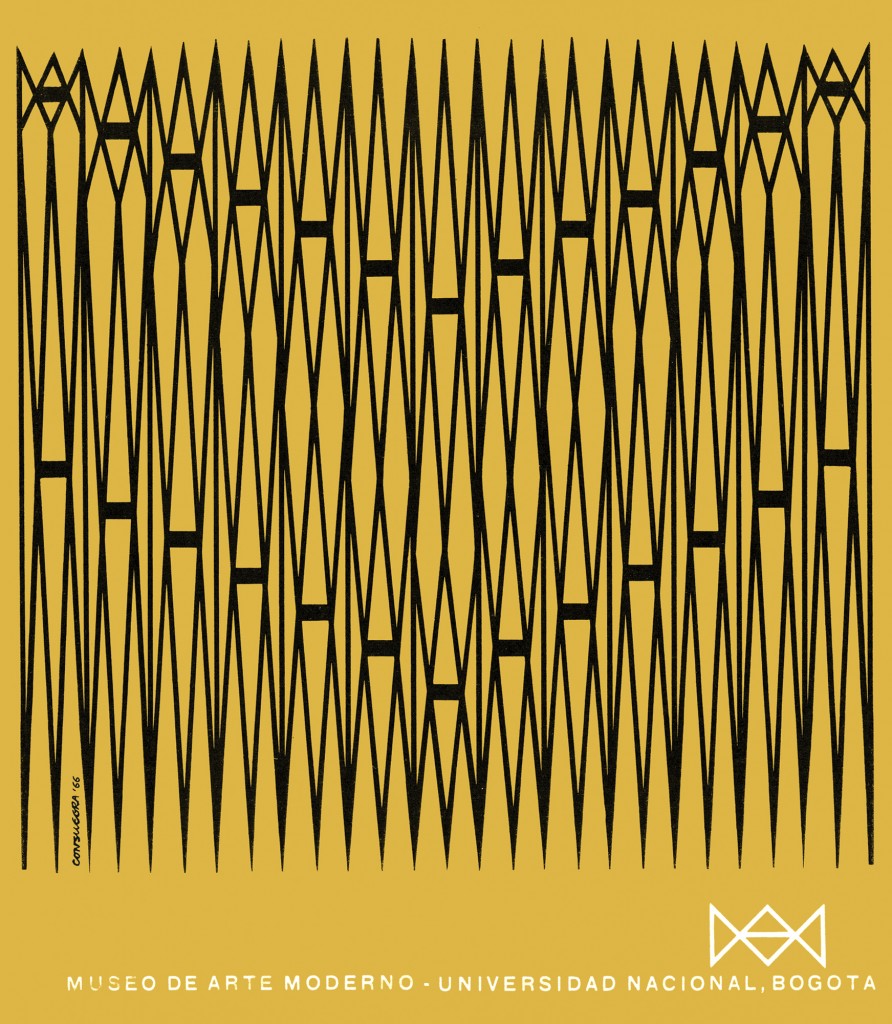

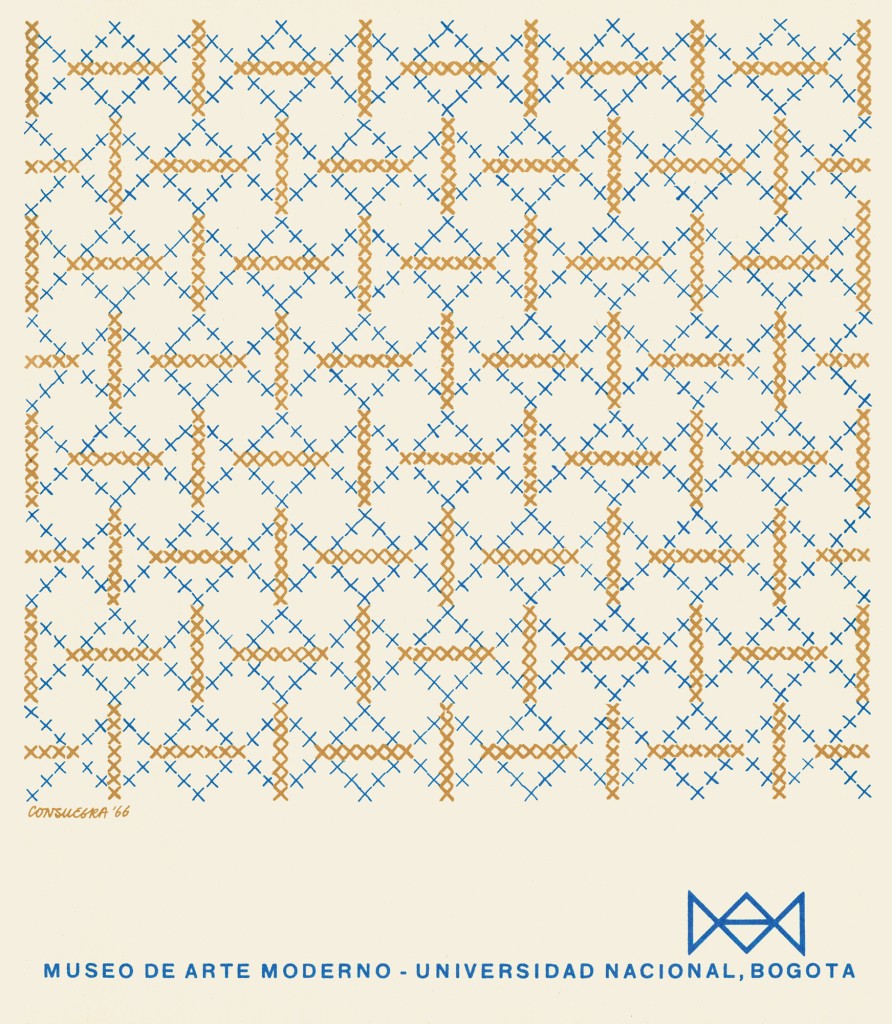

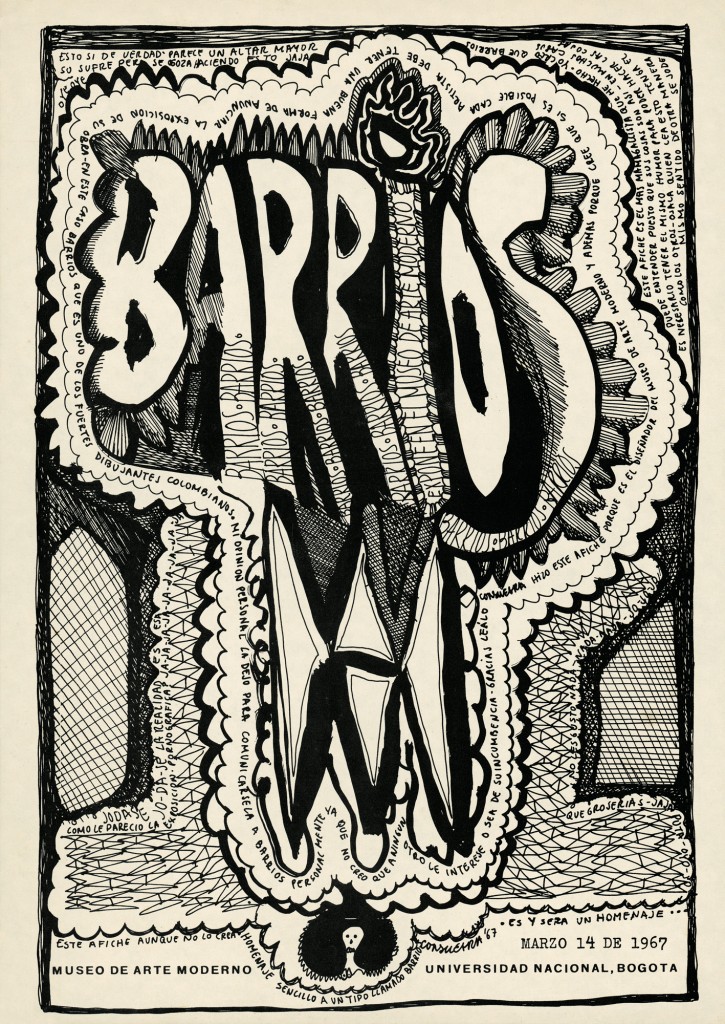

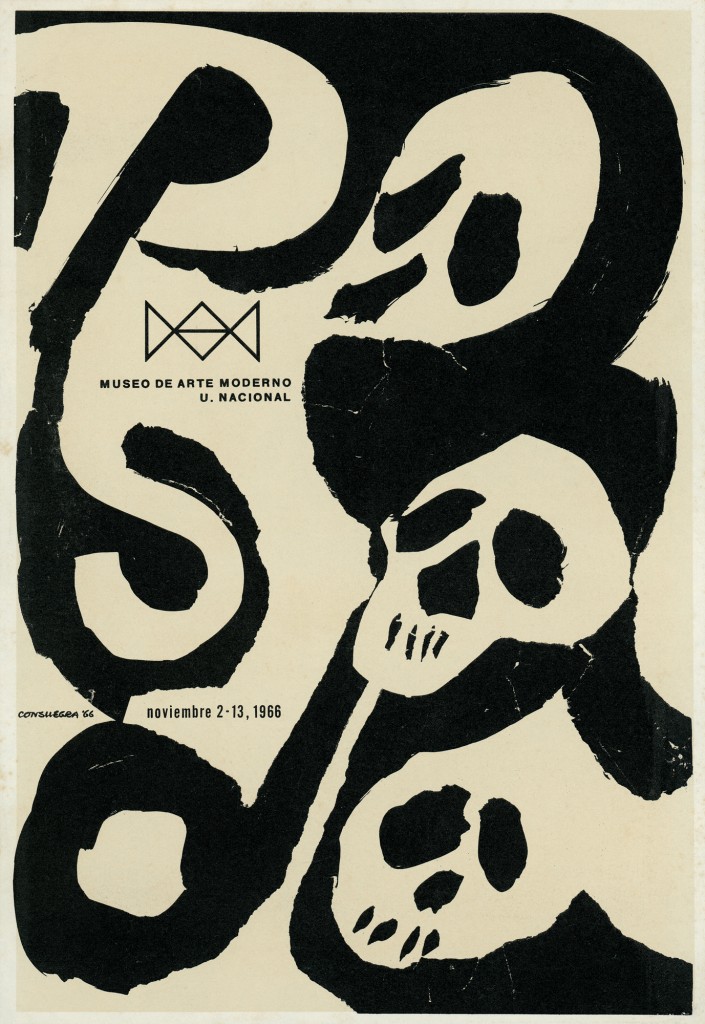

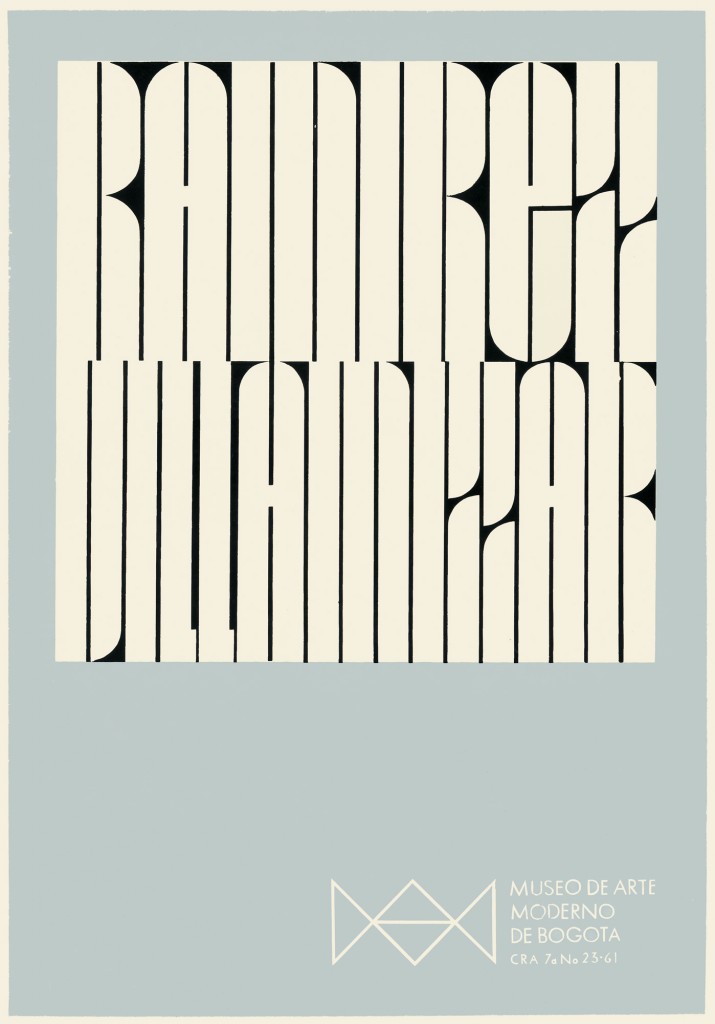

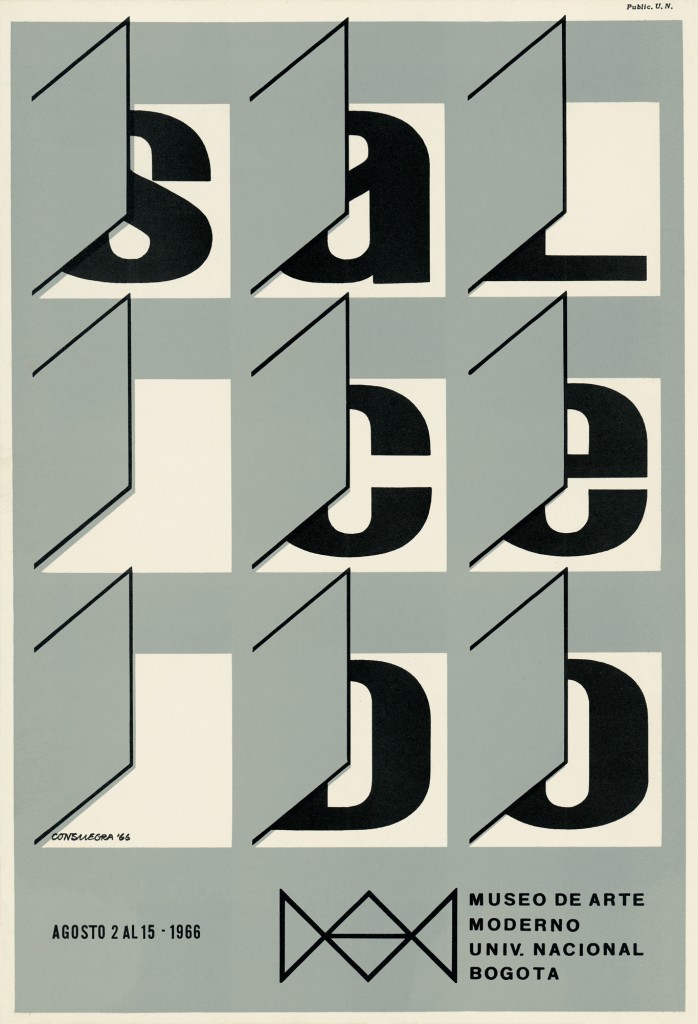

Drawings and posters ca. 1960–82

Various materials and dimensions

Courtesy of the David Consuegra Archive

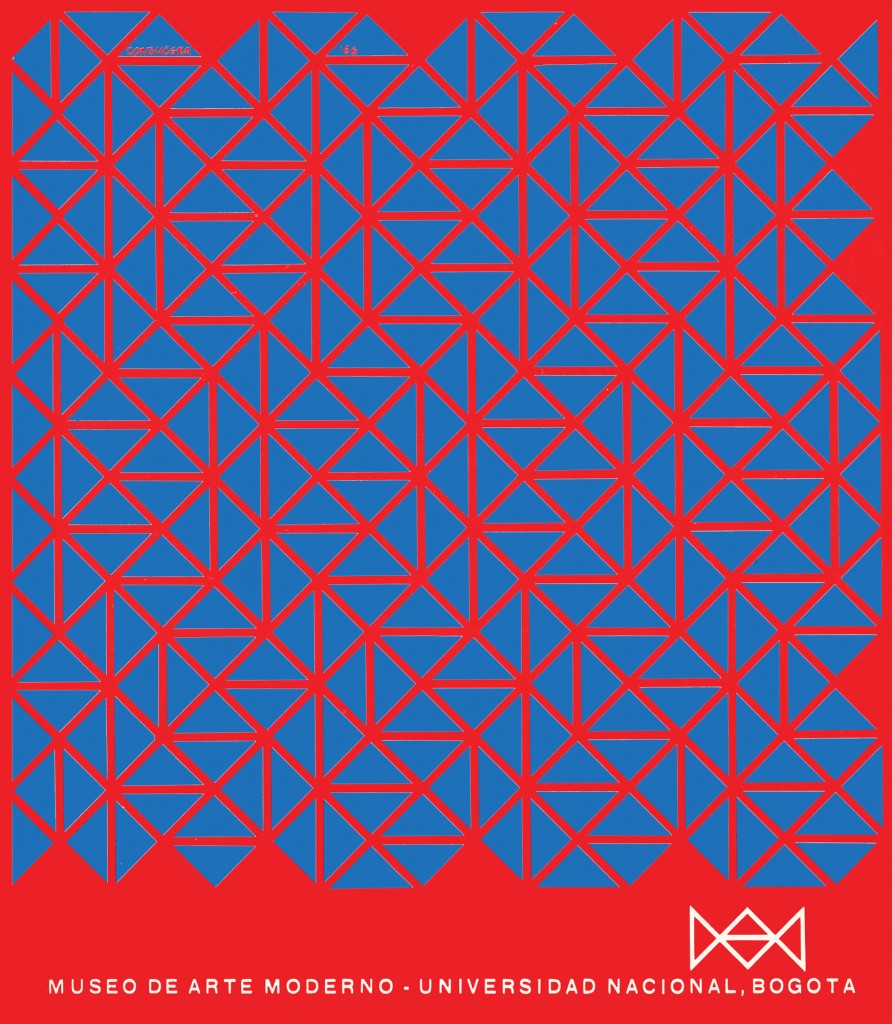

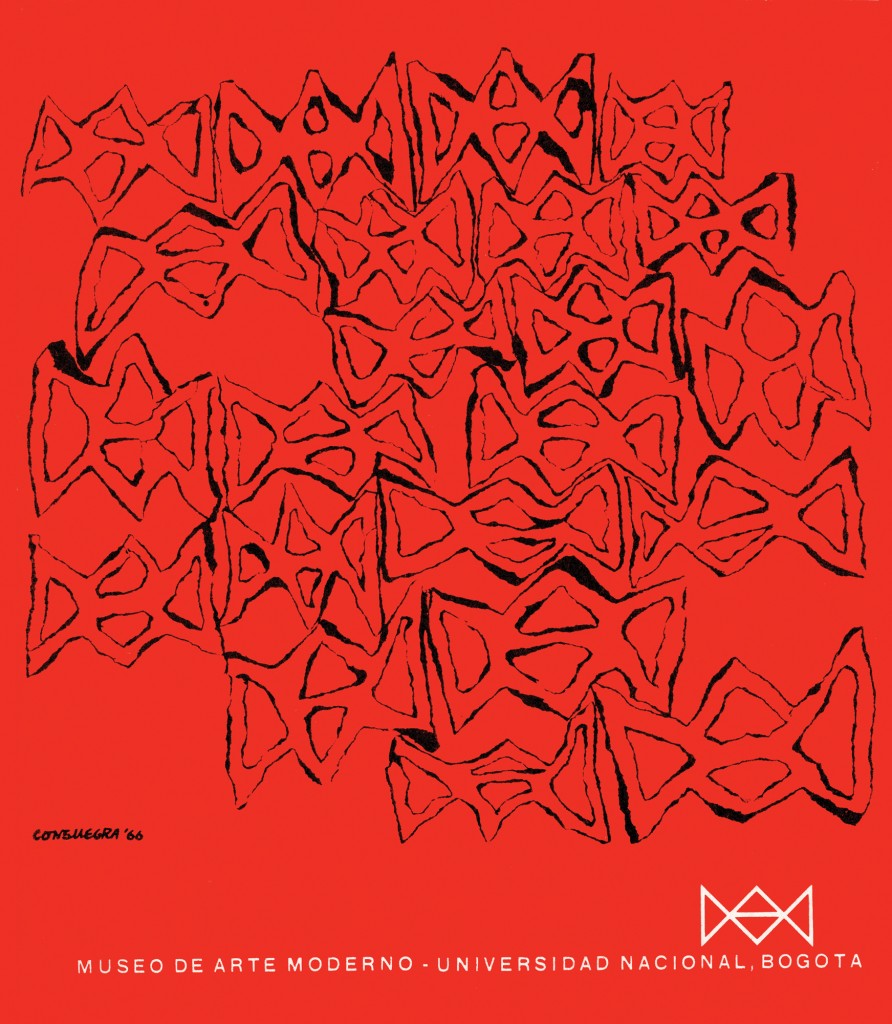

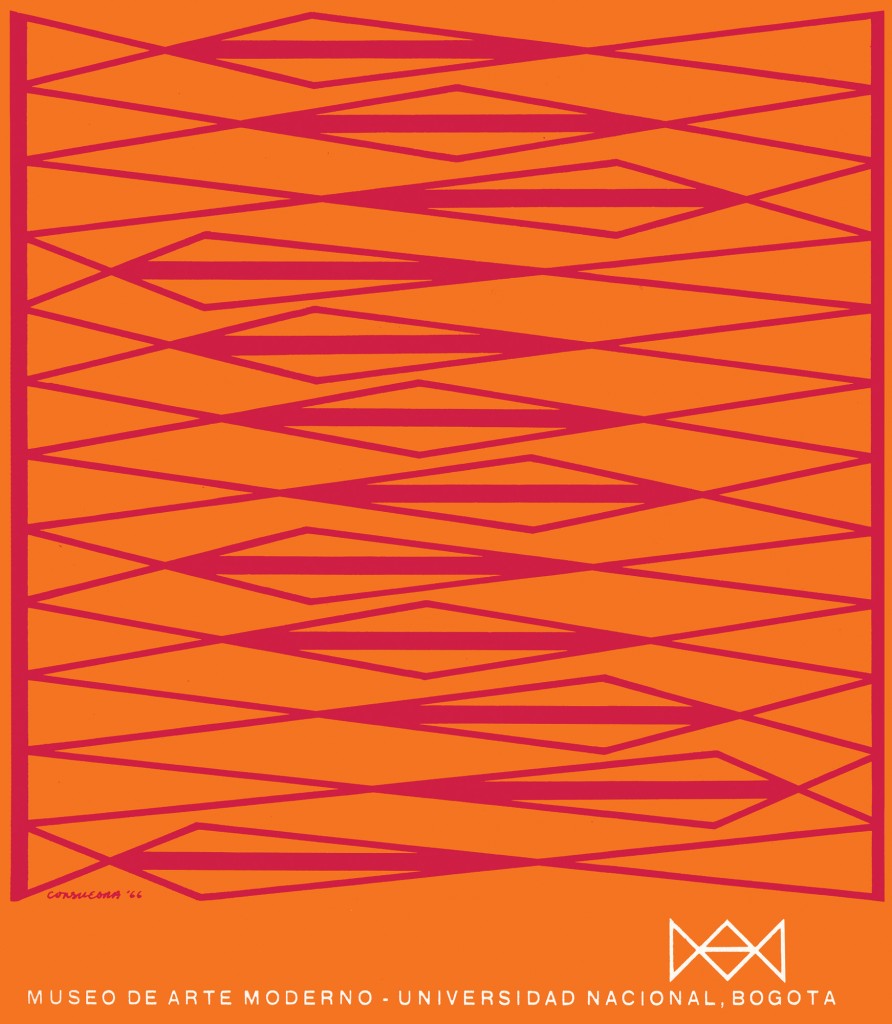

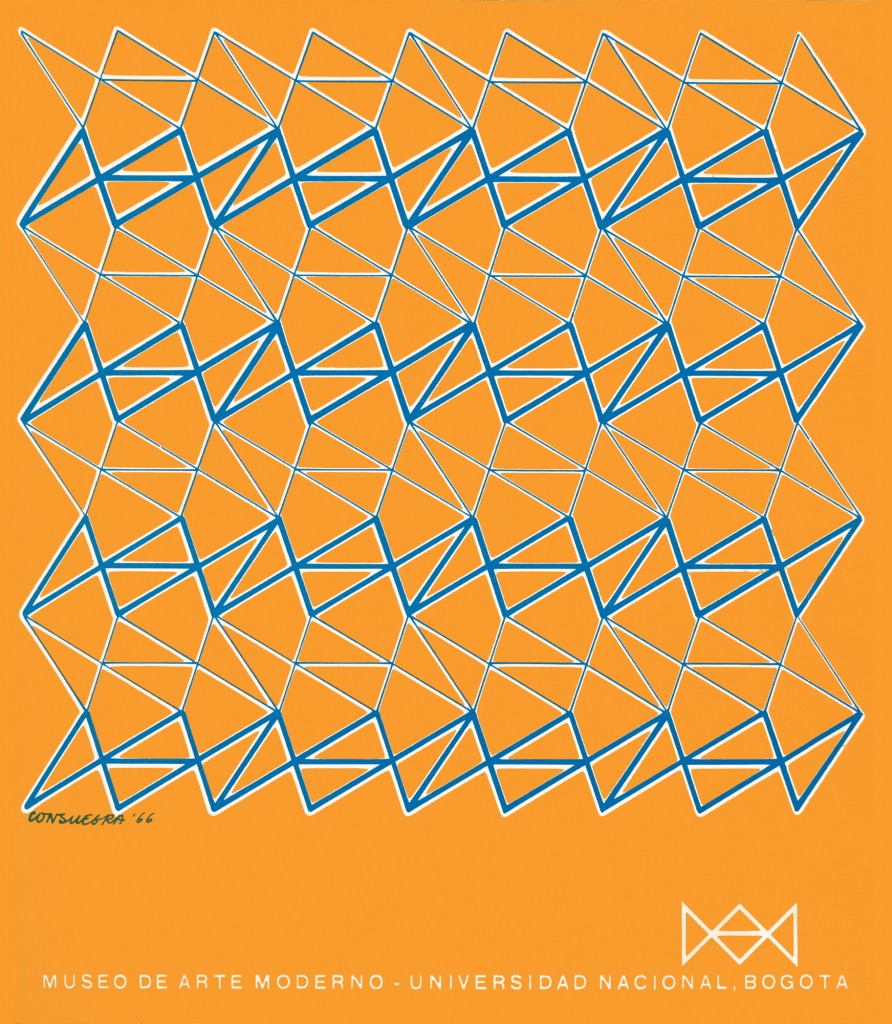

Many of the logos Consuegra designed are still in use today, while others are imprinted in the memories of most Colombians, such as those for Inravisión and Artesanías de Colombia. One of his most significant creations was the logo for Bogotá’s Museo de Arte Moderno (MAM). For this logo he proposed various geometric patterns based on his own penchant for openwork ornamentation. For MAM Consuegra also created a variety of provocative designs that exploited the virtually limitless potential of any given graphic pattern. His poster designs for various MAM solo exhibitions exercised considerable liberty in reinterpreting the work of each exhibited artist through his own illustrations and typography (another field that he pioneered in Colombia) while capturing their stylistic essence.

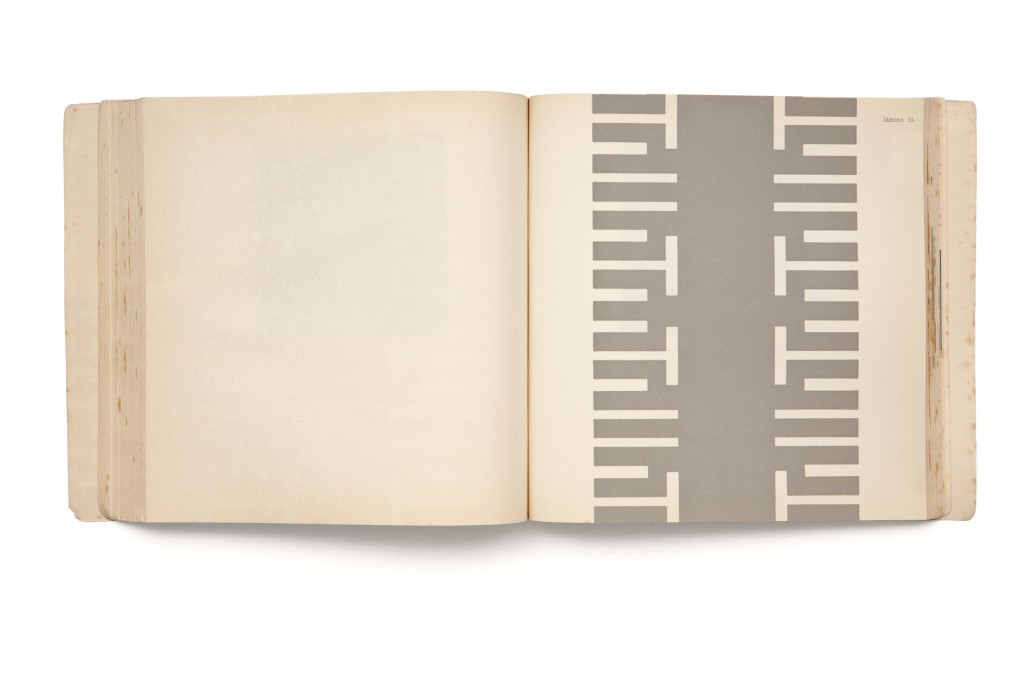

Book: 7 3/4 x 8 in. (19.5 x 20.5 cm)

“Through a formal analysis, we are able to understand that if a relationship existed between the two works it was created through a common vocabulary, such as the use of geometric elements or due to its being decorative openwork. But bearing in mind that within this same vocabulary there were significant differences, such as the use of acute angles instead of right angles, or the use of triangles instead of rectangles, we began with the structural analysis of the pieces. As such, we were able to determine that these elements were essential for both the appearance as well as the structure, which also aided in determining that the Muisca works had an impressionistic point of view while the Tolima works had an expressionistic point of view.

“By simultaneously analyzing form and content, we were able to perceive that the nature of the abstraction was found in the external form through geometric simplification, and in analyzing this form in order to understand that the arrangement of the components is its determinant factor, and moreover, that the ornamentation may have a primary purpose if it structurally replicates the piece that it is decorating.

“After having obtained this data, we were also able to determine that the artist is motivated in each expression by the relationship existing between himself and his work, and that based on this relationship both the piece and the decorative motifs have both an ornamental nature and a religious nature. That is the reason for there being dangling objects and crowns in the Muisca works, and in the Tolima works, tattoos and headdresses.”

— David Consuegra, Decorative Openwork in Pre-Colombian Indigenous Metalwork (Musica and Tolima)

![From <em>Ornamentación calada en la orfebrería indígena precolombina (Muisca y Tolima)</em> (<em>Decorative Openwork in Pre-Columbian Indigenous Metalwork [Muisca and Tolima]</em>). In collaboration with the Museo del Oro, Banco de la República. Bogotá: Ediciones Testimonio, 1968.](https://waterweavers.bgc.bard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/WW-010plate36_a-1024x696.jpg)

![From <em>Ornamentación calada en la orfebrería indígena precolombina (Muisca y Tolima)</em> (<em>Decorative Openwork in Pre-Columbian Indigenous Metalwork [Muisca and Tolima]</em>). In collaboration with the Museo del Oro, Banco de la República. Bogotá: Ediciones Testimonio, 1968.](https://waterweavers.bgc.bard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/WW-010plate36_b-1024x696.jpg)

![From <em>Ornamentación calada en la orfebrería indígena precolombina (Muisca y Tolima)</em> (<em>Decorative Openwork in Pre-Columbian Indigenous Metalwork [Muisca and Tolima]</em>). In collaboration with the Museo del Oro, Banco de la República. Bogotá: Ediciones Testimonio, 1968.](https://waterweavers.bgc.bard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/WW-010_26_flat-848x1024.jpg)

![From <em>Ornamentación calada en la orfebrería indígena precolombina (Muisca y Tolima)</em> (<em>Decorative Openwork in Pre-Columbian Indigenous Metalwork [Muisca and Tolima]</em>). In collaboration with the Museo del Oro, Banco de la República. Bogotá: Ediciones Testimonio, 1968.](https://waterweavers.bgc.bard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/WW-010plate18_b-1024x696.jpg)

![From <em>Ornamentación calada en la orfebrería indígena precolombina (Muisca y Tolima)</em> (<em>Decorative Openwork in Pre-Columbian Indigenous Metalwork [Muisca and Tolima]</em>). In collaboration with the Museo del Oro, Banco de la República. Bogotá: Ediciones Testimonio, 1968.](https://waterweavers.bgc.bard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/WW-010plate21_b-1024x696.jpg)

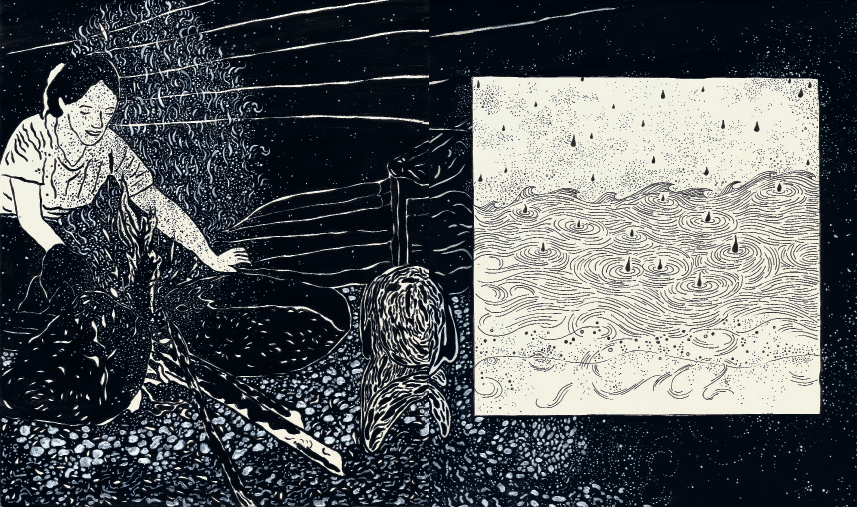

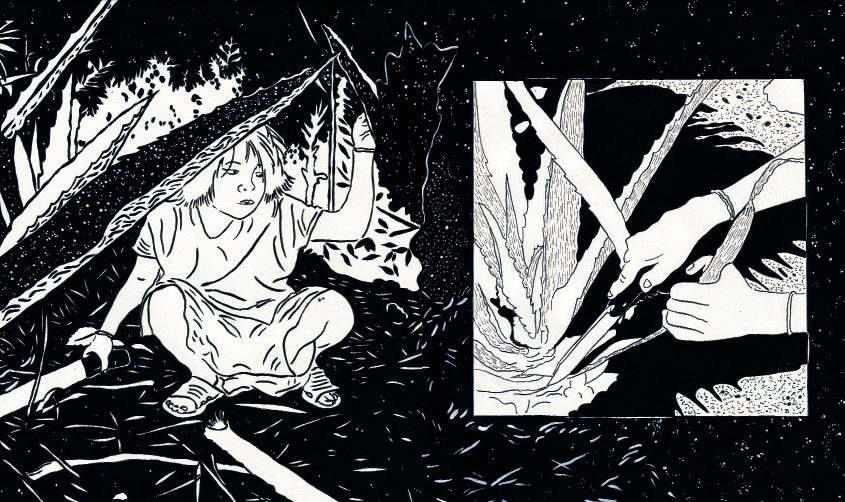

Ink on paper

“La Llorona” is a popular myth that appears throughout Latin America. Despite regional variations, the basic elements remain the same: a woman murders her children in revenge for her husband’s abuse; despairing, she begins to cry uncontrollably, and a river forms from her very tears. Indigenous groups, settlers, and immigrants in countries stretching from Argentina to Mexico have modified certain details, yet the figure of nature in mourning remains intact. María Isabel Rueda created her own version of this disturbing myth for a book titled La Llorona (2013), part of a group of publications about Colombian myths published by La Silueta Ediciones. In a series of drawings for the book, Rueda merged images of the Arhuacos (Ika), an indigenous culture of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta region of Colombia, with the Gothic imagery that characterizes her drawings, photography, and video works.

Video

Duration: 5 minutes, 7 seconds

Courtesy Juan Fernando Herrán and Nueveochenta Gallery

In Juan Fernando Herrán’s untitled 1993 video, a man walks in front of what appears to be a lake or a river. The camera zooms in on his head. He puts grass into his mouth and chews on it intently. This bodily operation goes on for several minutes. The camera zooms in further, focusing on the movement of his jaw muscles as more and more grass is chewed. Periodically, his mouth spits out green saliva. By the end of the video, a hand reaches to his lips; a small ball of green matter is produced and placed in the waiting hand like a gift, an offering. For most viewers, this process is completely unfamiliar. It could be a reflection on how nature becomes culture. Or it could concern the sculptural transformation of matter through the body, although what we usually understand as “sculpture” involves a material that is transformed with the hands.

7-channel video installation

Duration: Loop

The work itself takes the form of a paradox: various monitors project a succession of fixed perspectives, with a river that runs continuously from right to left, through the middle of each screen, where the horizon line would typically be. Shot in very similar light conditions, at different locations in the port of Honda on the Magdalena River, these moving photographs appear linked, creating the illusion of a single flowing image. Even if we are aware that what we see on one screen does not continue onto the next, we are deceived by the hypnotic flow of the river, and we cannot seem to escape the illusion of a single body of water. The water that flows out of one screen seems to be the same as that which enters the next.

Ceramic

Installation of 130 elements, overall: 17 ¾ x 19 ¾ x 171 ½ in. (45 x 50 x 436 cm)

Carol Young’s Memoria (Memory) consists of a long and somewhat dense series of thin ceramic sheets, each with its own unique folds and curves, like rocks, the veins in a cave, or a fissure in the land—each as individual as if created by nature. Yet all of the pieces fit together perfectly, unquestionably articulating an organic whole. Carefully mounted in an expansive installation, Memoria creates the impression of a fast-moving stream, with the curves evoking currents, and the arrangement of the pieces mimicking the movement of water rushing among stones.

Copper, werregue fiber

Two stools, each: 9 x 28 x 28 in. (22.86 x 71.12 x 71.12 cm)

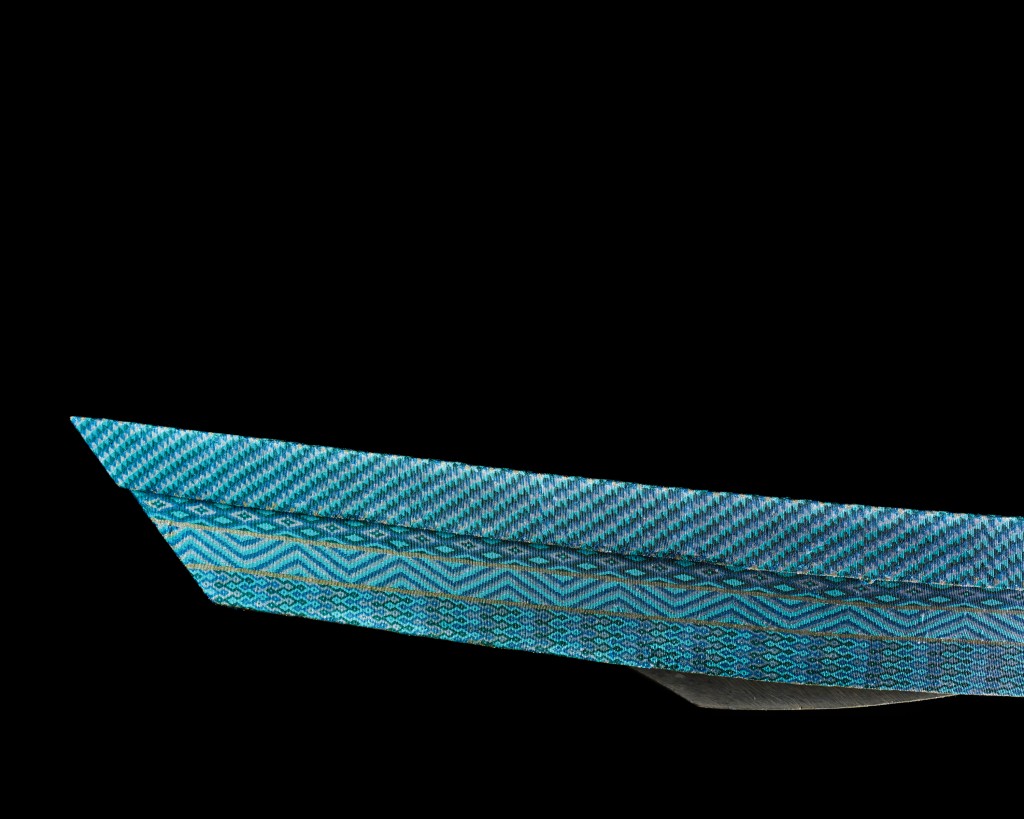

Wooden canoe, glass beads

11 x 29 ½ x 158 in. (28 x 75 x 401.3 cm)

In recent years, Lizarazo has been working with indigenous communities in the south of Colombia, in the state of Putumayo, a territory with great biological and cultural diversity. One such collaboration linked Lizarazo with the Inga people, an indigenous culture known for their intricate and colorful geometric patterns rendered with glass beads, usually for small-scale works such as jewelry. On one of his travels to the area, Lizarazo was able to acquire a canoe formerly used to transport coca leaves on the Putumayo River. The community was willing to sell the canoe to Lizarazo but was unaccustomed to treating their tools as commodities. They felt the need to regain their dignity after engaging in this kind of commercial activity and decided to give the boat a final “farewell” in the form of a “garment.” Thus an Inga family of eight came to the Hechizoo studio in 2013, where they stayed for almost half a year while painstakingly covering the outside surface of the boat with glass beads, expanding on their traditional patterns as they worked on a surface that was both familiar and, considering the task at hand, quite strange. The layers of traditional patterns covering the canoe correspond to specific images in the indigenous cosmogony: water, sky, and animals. “This canoe represents our environment, our traditions and our work: what we are,” said one of the proud craftsmen after they had finished this incredibly time-consuming work. This is the sense of dignity and pride that Lizarazo wants his pieces to convey.

Walking Jade area rug, 2013

Nylon monofilament, metal

168 x 168 in. (426.7 x 426.7 cm)

Jade textile, 2013

Acetate ribbon

56 x 70 in. (142.2 x 177.8 cm)

Neymar area rug, 2013

Fique fiber

59 ½ x 113 in. (151 x 287 cm)

Tree Surgeon, 2013

Rubber, patinated copper

125 x 24 x 12 in. (317.5 x 61 x 30.5 cm)

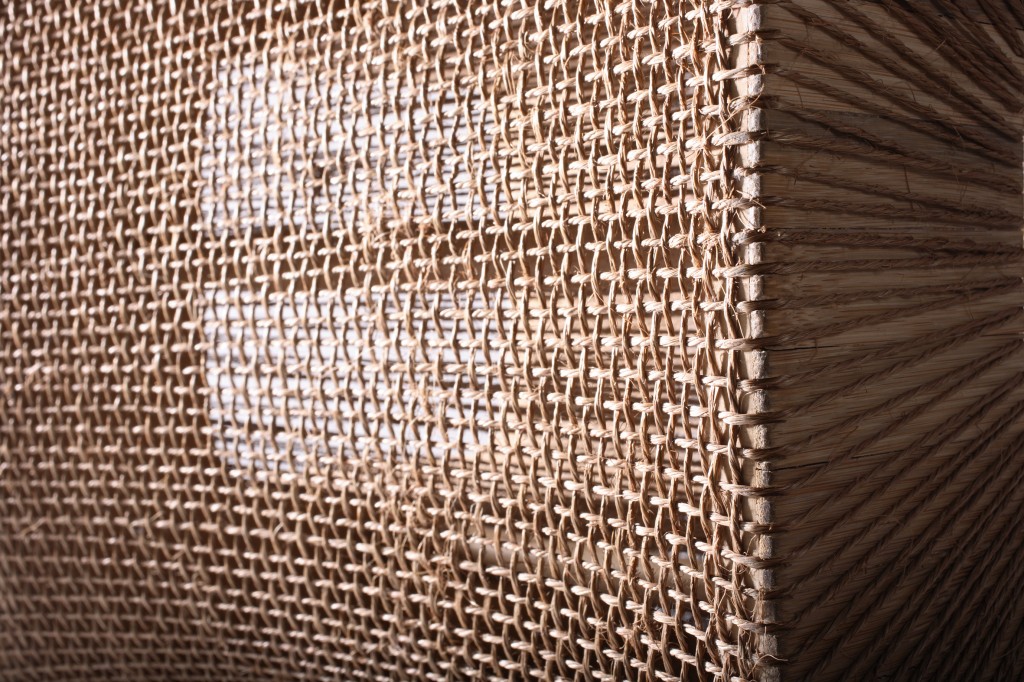

Jorge Lizarazo founded the textile workshop Hechizoo in 2000, and over the last fourteen years, he and his team of skilled colleagues (many of them trained by Lizarazo) have developed a truly innovative body of work with a deft mix of traditional and contemporary cultural references, materials, and techniques. The textiles they create mix natural fibers such as jute, raw silk, linen, and wool with materials seldom found in domestic textiles such as fishing line, copper or steel wire, twine, wrapping ribbon, glass rods, and twigs. In addition to working with more rarified materials, however, they also often “just take the same fibers available in the market and weave them differently,” as Lizarazo puts it. For Hechizoo, it’s a question of understanding and expanding the possibilities of textiles rather than merely taking advantage of the myriad new materials and techniques available through technology and the global market.

Recycled plastic, metal, paja de tetera fiber, wool

Set of 21, dimensions variable

“My initial inspiration for the design came after looking at an implement for removing the used tea leaves in Japanese tea ceremonies, which consisted of nothing but a piece of ‘stripped’ bamboo. I thought of transferring this technique to the bottle, with a weft and warp in plastic and natural fibers. By combining a global object like the PET bottle and a global craft like weaving, a fruitful encounter between design and handicrafts was created.”

— Alvaro Catalán de Ocón quoted in Loredana Mascheroni, “Autonomy by Design: Charting New Territories of Design,” Domus, no. 967 (March 2013)

Made by artisans from Curití, Colombia

Guadua bamboo, sisal fiber

Six stools, two of each type: 23 ⁵/₈ x 50 ⁵/₈ x 70½ in. (60 x 50 x 70 cm), 20 ½ x 17 ¾ x 16 ½ in. (52 x 45 x 42 cm), 13 ¾ x 23 ⁵/₈ x 7 x ⁷/₈ in. (35 x 60 x 20 cm)

The following manifesto was created by Sossella (graphic designer), Gualzetti (communication advisor), Simma (architect), and Salamanca (designer) in 2003.

Fair Trade Design

Gabriele Sossella, Ludovico Gualzetti, Benno Simma, and Lucy Salamanca

Fair Trade Design Goals

Fair Trade Design Principles

Fair Trade Design Values

Doble curva (Double curve) chairs 1 & 2, ca. 1990

Guadua bamboo roots, saddle leather, cast-bronze

47 ¼ x 31 ½ x 31 ½ in. (120 x 80 x 80 cm)

Bamba chair, ca. 1990

Nato tree roots (Mora excelsa)

47 ¼ x 39 ³/₈ x 31 ½ in. (120 x 100 x 80 cm)

The chairs produced by Marcelo Villegas are surprising not only for their expressionist qualities but also for their extremely simple and modern structural refinement. Instead of molding wood or metal to a specific shape, Villegas uses the natural curves in guadua bamboo, selecting perfect sections with which to build his powerful creations. The guadua root surfaces, which are coarse and full of texture, evoke the wrinkled hides of certain animals, so that each chair emits the sense of a living being with an imposing presence.

Video installation

Duration: 14 minutes

Clemencia Echeverri Estudio

“Some rivers in Colombia have been, in their silent course, witnesses to a history that we reiterate tirelessly: an endless flow of all that we attempt to redress or amend. In Treno, a video installation developed on the banks of the Cauca River (in the environs of the Caldas and Antioquia Provinces) with local people, I put on an event whereby the moving image and sound bring into focus a time that the place itself keeps silent. Notwithstanding its apparent nature as a scenic viewpoint, a resting place, a natural wonder, the river carries unheard and errant voices; the juxtaposed experiences of a country that proposes and attempts its reconstruction at every step, while it is dragged down by a history that is tied to horror. I create a dialogue by way of two confronting projections that highlight discord and disintegration as constants that hamper the construction and that point to the void instead: an unanswered plea that speaks, indeed, of hopelessness.”

— Clemencia Echeverri

Yaré fiber

29 ½ x 29 ½ x 59 in (75 x 75 x 150 cm)

Courtesy of Tropenbos International, Colombia

The fish trap captures the beauty of natural materials and evokes the functional logic of a traditional form.

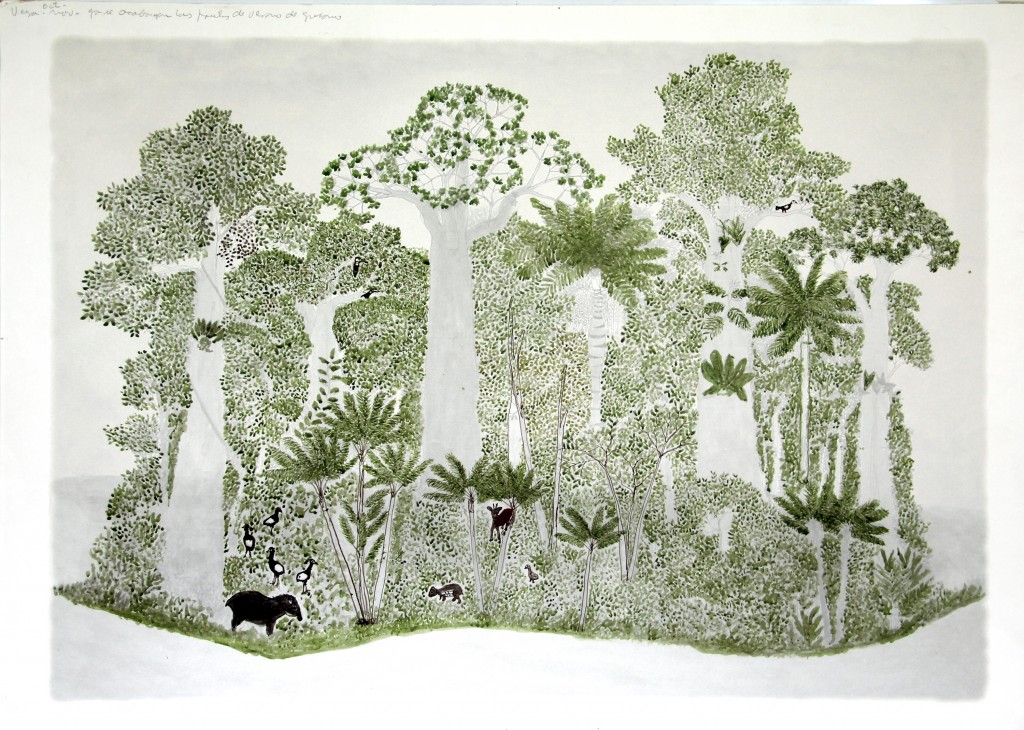

Ink and watercolor on paper

47 ¼ x 39 ³/₈ in. (120 x 100 cm)

Courtesy of Tropenbos International Colombia

“The Creator made the fruit tree, not only with wild fruits, but also with those that were edible. No one knew that the tree was there and that it produced many types of fruit. The fruit began to fall, because now it was ripe, but no one noticed. Those living in these areas suffered hunger, but they sensed that there had to be something to eat. . . After much discussion, the people went out into the forest to look for food, and they noticed that this tree existed, and they gathered some seeds and other fruits but they didn’t know if they could eat them, they were afraid, the fruit was likely poisonous. They licked the fruit, sensing the sweetness and the other flavors, but they didn’t know if they could be eaten. They returned to the others and told them what they had found. Everyone went to see, and it was true—there were different kinds of fruits, some in bunches, some with seeds, depending on the branch from which they hung. They wondered how they could get them down from the tree, whether they should climb up, whether the tree could be cut down, but they didn’t know. So they waited until the fruit fell by its own, and then they ate it.”

— Abel Rodríguez, “Looking with Words, Looking with Stories,” by Catalina Vargas Tovar

Ink and watercolor over digital print on paper

12 drawings, each: 19 ¾ x 27 ½ in. (50 x 70 cm)

Courtesy of Tropenbos International Colombia

“This painting includes the larger trees, such as the marañón and the higuerón, and various seed- and fruit-producing trees eaten by animals, which are painted first. Then come the smaller trees, such as the açai palm, the large guama, a carguero de dormilón, another larger lecythis, the sangre toro, and the bombona and yavarí palms. The small ones give depth to the mountain, in my opinion. When the river is high, these lowlands are flooded, and so all the animals that would usually be here, are now in higher parts. During the summer months (December and January), fish start going up the river because they know that the water is going to rise, and they’re looking for the overflows to enjoy the abundance of worms and seeds. When the waters begin to rise, worms are brought out of the ground, and the fish eat them; the other animals begin to migrate further into the forest. The monkeys stay because they like to look at their reflection, as ugly as it is, in the water. They descend along the lower branches and approach the water’s edge; and then see that there’s another monkey down there. That’s how they amuse themselves. That’s why, when the river is high, you’ll see more monkeys by the river than you will in higher areas.”

— Abel Rodríguez, “Looking with Words, Looking with Stories,” by Catalina Vargas Tovar

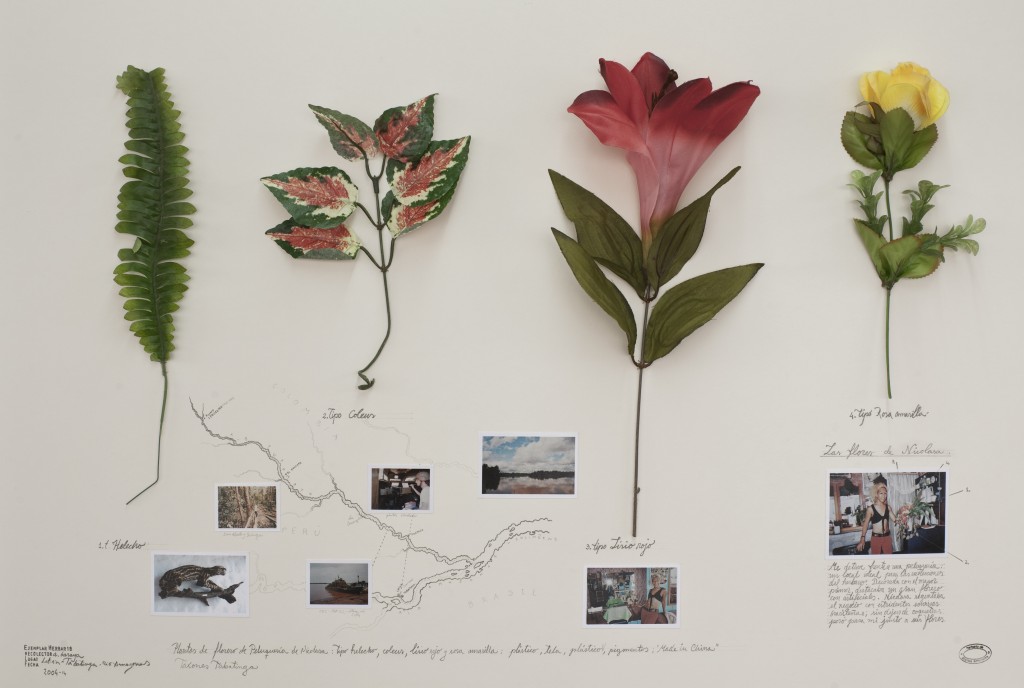

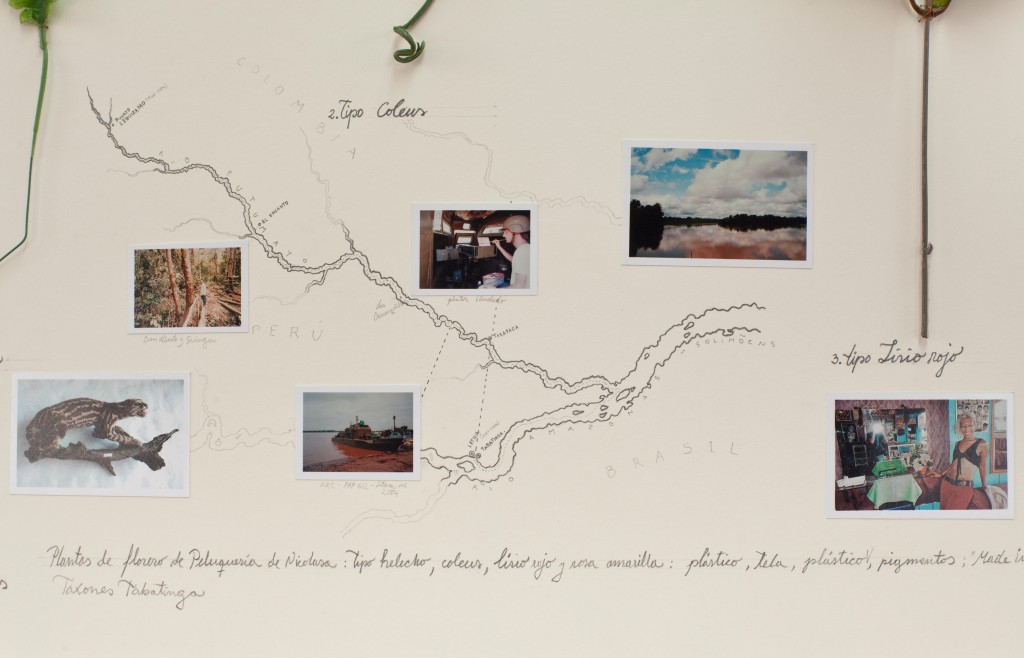

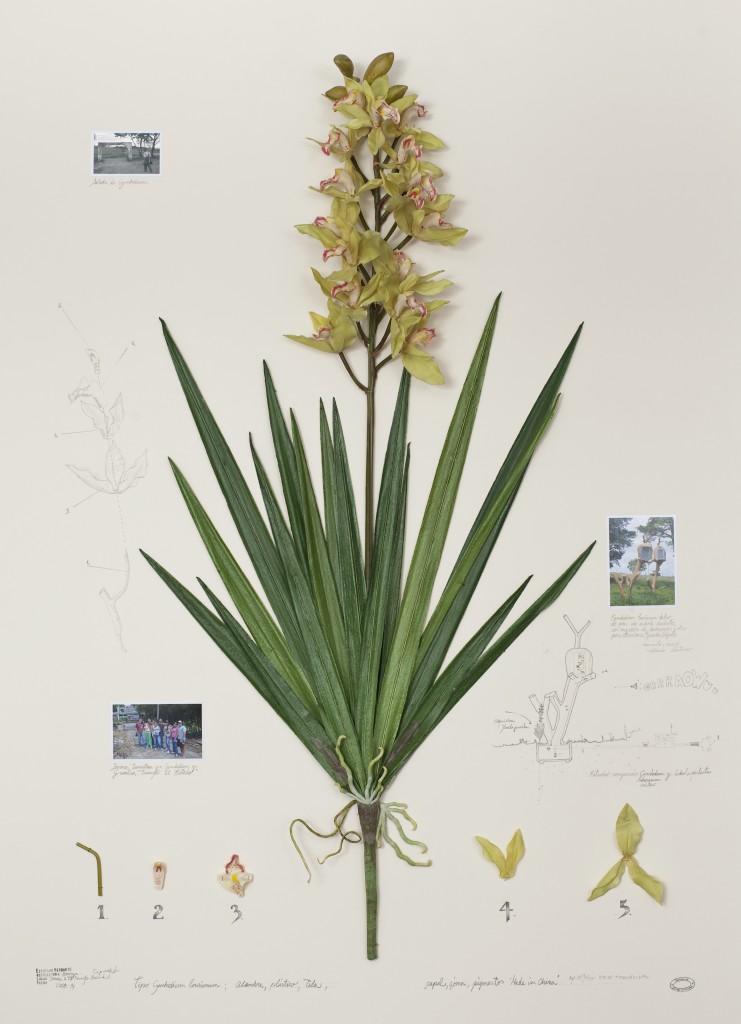

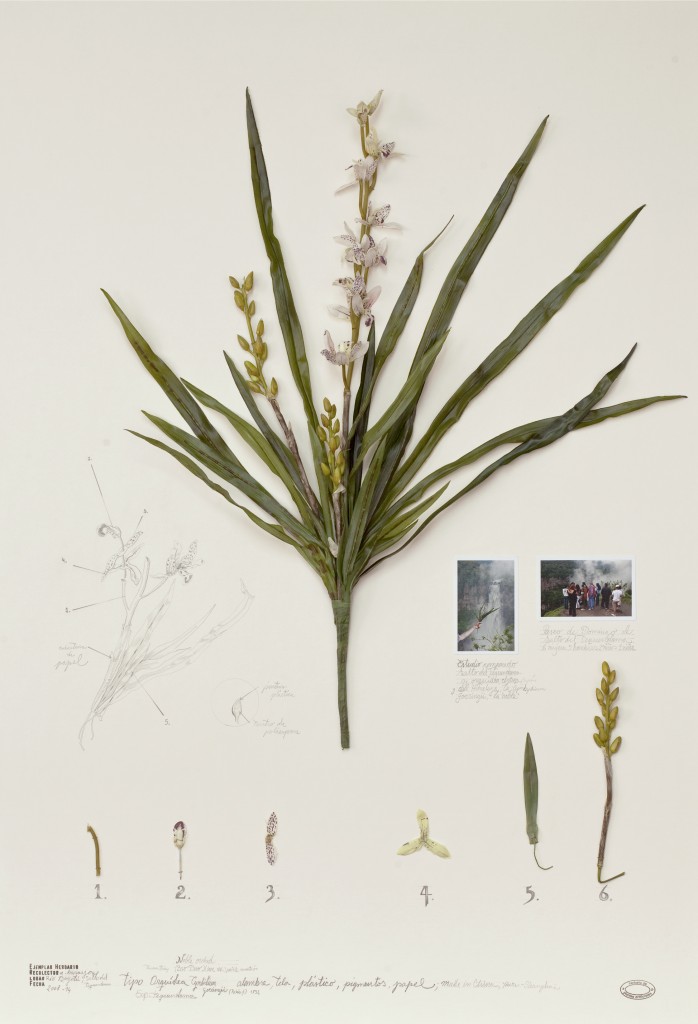

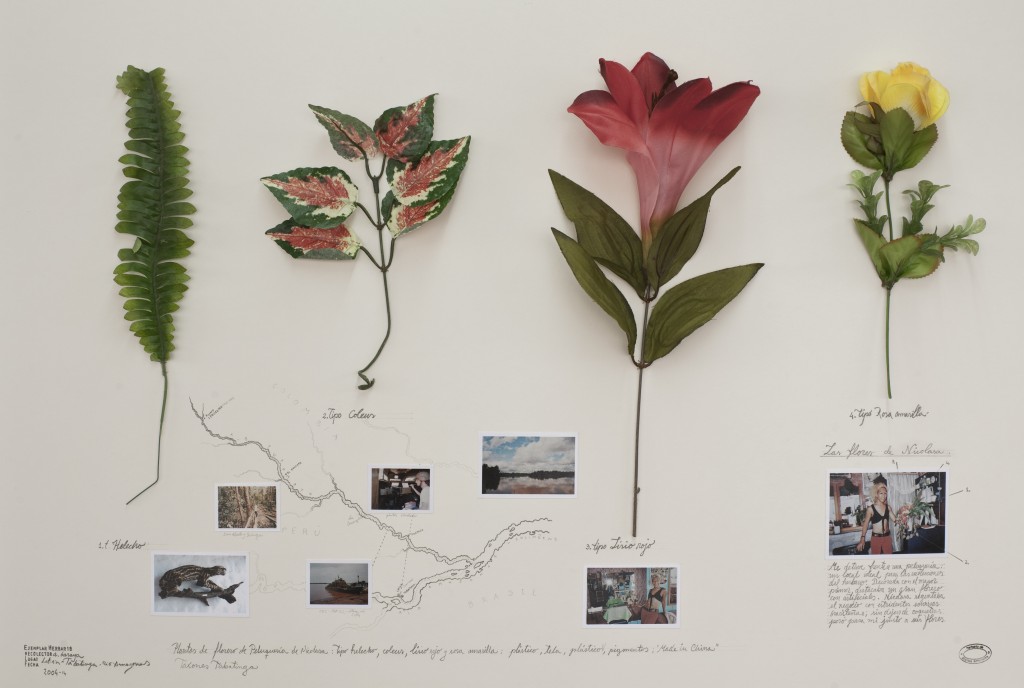

Found objects “Made in China,” pencil, photography on cardboard

Tabatinga taxons

22 x 32 ¼ x 2 in. (56 x 82 x 5 cm)

Orquidea Cymbidium lowianum napoles

(Cymbidium lowianum napoles orchid)

44 x 32 ¼ x 2 in. (112 x 82 x 5 cm)

Orquidea Tequendama

(Tequendama orchid)

32 ¼ x 22 x 2 in. (82 x 56 x 5 cm)

“I have been traveling around the world for many years, collecting plastic plants from waiting rooms, homes, restrooms, cafés, and airports on a pseudo-botanical expedition inspired by the likes of the eighteenth-century Spanish botanist José Celestino Mutis. Finally, at the end of last year, I was able to travel down the Amazon collecting more species of ‘Made in China’ for my herbarium of artificial plants.”

— Alberto Baraya, “Reading One River on the River”

Árbol histórico (Historical tree) and Rama B (Branch B)

from Proyecto del árbol de caucho (Rubber tree project), 2005

Rubber

Árbol histórico: 137 ⁷/₈ x 98 ¹/₂ x 7 ⁷/₈ in. (350 x 250 x 20 cm)

Rama B: 196 ⁷/₈ x 118 ¹/₈ x 4 in. (500 x 300 x 10 cm)

For the São Paulo Biennial in 2006, Baraya spent three months in the Amazonian state of Acre, whose post-colonial history was shaped by the rubber boom in the nineteenth century. Baraya reversed the process of material exploitation and, with the help of former seringueiros (rubber tappers), he painstakingly covered the whole surface of a 30-meter-tall rubber tree with latex taken from similar trees. Once the latex solidified, it was peeled off and laid on the ground, like the discarded skin of a giant snake. Here was a life-size cast of a lost cultural practice that fostered the decimation of the indigenous populations, the virtual slavery of migrant workers from the drought-stricken north, and the political transformation of an enormous territory.

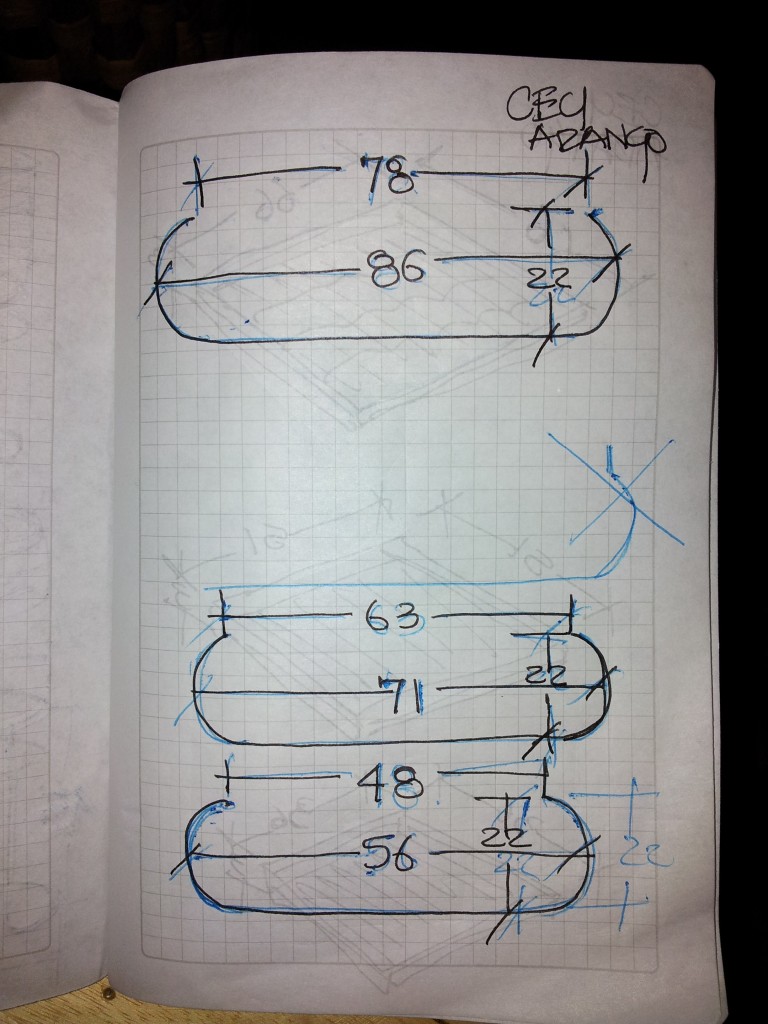

Corocora stools, 1993

Woven by artisans from the Guacamayas community in Colombia

Fique fiber spiral-woven over esparto fiber, macana palm wood base

Six stools, two of each type: 28 x diam. 17 in. (71.12 x 43.18 cm), 20 x diam. 16 in. (50.8 x 40.64 cm), 12 x diam. 16 in. (30.48 x 40.64 cm)

Cucarachero poufs, 2014

Woven by artisans from the Guacamayas community in Colombia

Junco fiber spiral-woven over wood structure, macana palm wood base

Two poufs, each: 10 x 36 x 36 in. (25.4 x 91.4 x 91.4 cm)

Arango often works with craftsmen and craftswomen, taking advantage of given traditional forms or modes of production and changing them slightly to better suit the requirements of her designs. The Corocora stool, designed in 1993 and in production ever since, takes its name from the scarlet ibis, a bird commonly found in Colombia. The long legs and colorful seat of the stool brings to mind the ibis when seen from a distance. Arango acquainted herself with a spiral weaving process typical of several communities in Colombia, in which a core of esparto fibers is wrapped in fine fique thread and becomes a tubular form that can be stitched together following an outward spiral.

Video installation

Duration: 5 minutes

Monika Bravo’s video installation is inspired by a traditional pattern of the Arhuaco people, a cultural group native to the mountainous Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta region adjacent to the Caribbean coast of Colombia. Working from a mathematical analysis of the way in which Arhuaco women weave their patterns, Bravo replicates their designs by constructing the textile digitally, using pixels as her “threads.” Bravo’s digital weaving eventually morphs into the landscape of the Sierra Nevada.

Video

Duration: 1 minute, 50 seconds

“The boat sailed from Cartagena, where it was built, along the entire Atlantic coast of Venezuela, the Guianas, and Brazil, and up into the Amazon River. As it happened, I would be on this boat, documenting its journey for the Centro de Integración Fluvial de Sur América, (The South American River Integration Center, CIFSA). My job was to film the Putumayo to assess its navigability, as well as the flora along its banks, its fauna, the local people, and other travelers we crossed paths with. I would also be carrying out interviews in ports along the way, and chronicling the events of the journey. (…) The monotonous scenery of the two-week journey was enlivened by the flocks of macaws, by reading through the pages of One River, by the squawking of the parrots, and by the wild animals that I imagined lurking behind every tree. In one port, I visited a maloca, the large communal home of the indigenous tribes. There was no spectacle there. The mambeo gatherings, where people were chewing coca leaves, or the ceremonies for imbibing the hallucinogenic plant infusion known as yagé, were exactly as Davis had described. I saw an extremely old rubber tree, was given a cacao pod, and bought a pineapple that for some reason aroused great hilarity among the crew. In the evenings, I went up on the roof and indulged my romantic urges with a brush, a box of oil paints, and some small canvases. I painted the clouds, the reflections on the river, and the distant lines of trees, while musing on the art of painting itself. One afternoon, passing in front of the place called ‘Las Barranquillas,’ the 611 ARC Tony Pastrana river patrol ship slowed down so that the crew could practice firing their 50-caliber SS Galil assault rifles. As all the marines emptied their cartridges into the water, I was up of the roof, filming the explosions, the splashing of the bullets on the mirror-like surface of the river. After that, I began incorporating the lines made by the bullets into my idle, Sunday afternoon landscape painting.”

— Alberto Baraya, “Reading One River on the River”

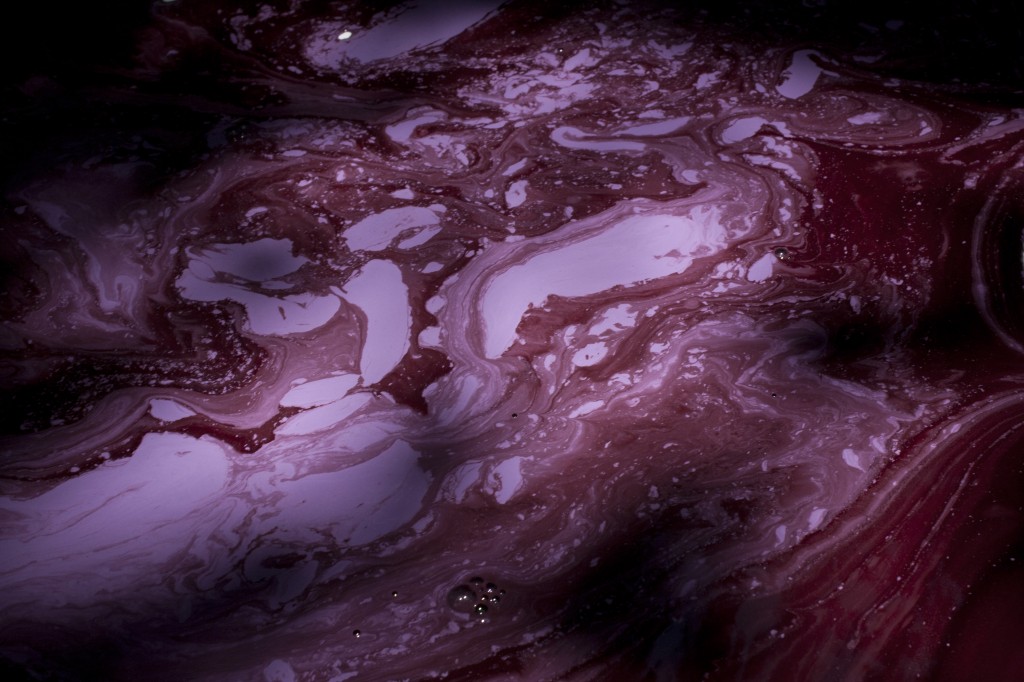

Paper and fique fibers tinted with natural dyes, flat file with monotypes

30 tinted papers, each: 40 ¹/₈ x 26 ¾ in. (102 x 68 cm)

220 bundles of tinted fique fibers: various dimension

10 monotypes, each 39 ³/₈ x 25 ⁵/₈ (100 x 65 cm)

“Susana Mejía has been enthralled with one of the most fascinating aspects of this infinite region: the plants and processes used to extract innumerable colors from their parts (the plant’s bark, leaves, fruit, sap). With her sense of curiosity and wonder, she has convinced some indigenous women to reveal their ancestral secrets to her, and from them has learned how to extract a chromatic range from the vegetation that replicates the variety found across the entire territory. She has created a beautiful expedition in color on textiles, fiber, and paper that, almost unintentionally, has become a work of art; a work of art that combines ecology, geography, color, and the beauty of form.

“She has taken a fragment of the whole, and what is wondrous is that in that fragment—as in a poet’s use of synecdoche—the whole seems to be reflected. Within that massive noise, she has identified a melody of colors. She is someone who, in extracting the essence of a liquid, root, leaf, or fruit, has released a type of alkaloid that is not harmful—that is the most pure and evocative essence of our rainforests: the chromatic range of that ever-present green that turns, as if by magic, into an infinite spectrum.”

— Héctor Abad Faciolince

Achiote

Achiote, annato, cocote, bija, bixa, onnote, urucú

Bixa orellana

Family: Bixaceae

Order: Malvales

A red color is extracted by rubbing the seeds. The yellow-fruit variety of achiote was the kind chosen this time. It is considered low-yielding in dye, since abundant fruit is necessary for the extraction of color pigment. The extract adheres well to paper; the intensity of the color diminishes and becomes softer when applied to fique and cotton.

General Description

Woody shrub or small, leafy tree with spreading branches, which may grow between ten to thirty-two feet (three to ten meters) in height. It has heart-shaped leaves, with white or pink flowers that cluster at the ends of its branches. The fruit is oval-shaped, with long, rigid bristles that range from reddish to brownish tones. Its conical seeds may be yellow or red, covered by a layer of bixin, the substance that gives it its pigment.

Geographic Distribution and Natural History

A native of tropical America. Although it is grown in other parts of the world, its main concentration is still in Latin America and the Caribbean, where it has been cultivated since pre-Hispanic times. The achiote shrub grows rapidly, can be used ornamentally, and is found primarily in warm climates in the foothills of mountains.

Uses

The achiote seeds contain a natural dye that has multiple uses. Traditionally, different indigenous communities used this dye to paint and tattoo the body, as insect repellent, sunscreen, and lip balm. This pigment is also used to dye textiles, decorate kitchen utensils, and, in food, as a condiment.

— Plant description by Paulo Pulgarín. From Susana Mejía, Color AmazoniaColor Amazonia (Bogatá: Mesa, 2013), 34–36.

Linen, gesso, acrylic

114 ¼ x 11 ¾ in. (290 x 30 cm)

Courtesy Nohra Haime

Nudo azul XIII (Blue knot XIII) was conceived by de Amaral as a commentary on the medium, a single knot that unites the threads and constitutes the basic act of textile creation. The piece hangs from the ceiling, its fibers gently cascading to the floor, bringing to mind a stream of water, seeming at the same time to flow sensuously and to be forever petrified.

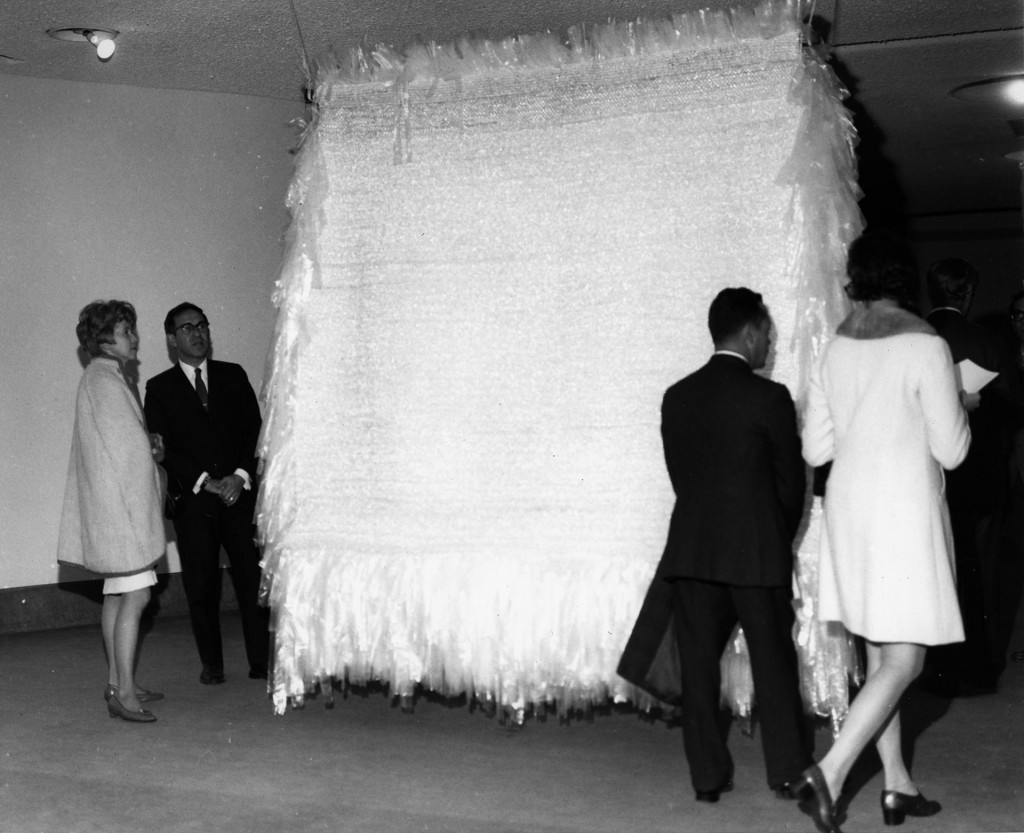

Woven plastic

137 ¾ x 61 in. (350 x 155 cm)

Luz blanca (White light) was created by knotting strips of narrow, flat, clear plastic to a backing in successive layers until it became a rich silver-white wall hanging that belies the humbleness of its materials. Created with cheap plastic wrapping that yellows rapidly, the piece has been redone twice since the first version in 1969, as if to underline its conceptual nature. From a distance, it recalls a waterfall in its shimmering interplay of light and reflection.

Source: http://guajiraturismo.wordpress.com/guajira-magica-y-exotica-4/

“La Llorona” is a popular myth that appears throughout Latin America. Despite regional variations, the basic elements remain the same: a woman murders her children in revenge for her husband’s abuse; despairing, she begins to cry uncontrollably, and a river forms from her very tears. Indigenous groups, settlers, and immigrants in countries stretching from Argentina to Mexico have modified certain details, yet the figure of nature in mourning remains intact. María Isabel Rueda created her own version of this disturbing myth for a book titled La Llorona, part of a group of publications about Colombian myths published by La Silueta Ediciones. In a series of drawings for the book, Rueda merged images of the Arhuacos (Ika), an indigenous culture of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta region of Colombia, with the Gothic imagery that characterizes her drawings, photography, and video works.

In Rueda’s visual depiction of the story, we see the key to this joining of the words water and weavers. Here there are the fundamental elements of textile: plant stalks (from which fibers are extracted), threads, a weaver, mochilas (bags traditionally woven by the Arhuaco), and various graphic motifs used in textile design. To these facets are added the different forms assumed by water, and, inevitably, the tears of the weeping woman, which are depicted as drops, stars, and diamonds. The narrative progresses, building, scene by scene, into a single, continuous image: that of a great river connecting all of these elements, in which each motif has two or three meanings and serves as an icon for some mystical or romantic ideal.

Over more than twenty years, Rueda has created a singular body of work that intertwines the Gothic with the tropical. In the 1970s, a range of Colombian authors and filmmakers—most notably Carlos Mayolo, Luis Ospina, Andrés Caicedo, and Álvaro Mutis—were also combining these two forms, but with very different results. For them, the tropics were a lush, hot, confusing environment into which the Gothic brought vampires and occult forces. In Rueda’s works, the Gothic refers to highly stylized and melancholy black-andwhite imagery, which, when introduced into the tropical environment, appears as absurd, thus transporting romantic chiaroscuro from its Northern sources and framing it within a completely different geographical context.

Ultimately, Rueda’s conceptualization of “Tropical Gothic” continually resonates with these two distinct sensibilities, compelling the viewer to see beyond the purely material and pragmatic; to understand how the rivers, plants, threads, textiles, mochilas, and coca—as well as the underlying mournful weeping—are all imbued with their own spiritual force, even if this force seems to lie beyond what many today seem capable of understanding.

Rueda’s interpretation ask us to take seriously the challenges posed by life in the Sierra Nevada, and also open ourselves up to doubt contemporary, scientific convictions. The indigenous peoples who inhabit that region see themselves as our older siblings and consider us children who do not understand the implications of our actions. The calamities that we have wrought through the abuse and destruction of the environment also cast doubts on our integrity as a society, especially given how the indigenous cultures have been able to live harmoniously with nature, a relationship in which rituals, myths, and respect for the wisdom of the Mamas (shamans) has guided their actions along very different paths.

Rueda spent much of her formative years in cities. Today she lives by the sea, and through her work she strives to maintain a deep connection to her environment, to not lose the capacity to communicate with people who see the world very differently from what is now conventional.

Translated by David Auerbach.

In Juan Fernando Herrán’s untitled 1993 video, a man walks in front of what appears to be a lake or a river. The camera zooms in on his head. He puts grass into his mouth and chews on it intently. This bodily operation goes on for several minutes. The camera zooms in further, focusing on the movement of his jaw muscles as more and more grass is chewed. Periodically, his mouth spits out green saliva. By the end of the video, a hand reaches to his lips; a small ball of green matter is produced and placed in the waiting hand like a gift, an offering. For most viewers, this process is completely unfamiliar. It could be a reflection on how nature becomes culture. Or it could concern the sculptural transformation of matter through the body, although what we usually understand as “sculpture” involves a material that is transformed with the hands.

But for those familiar with indigenous communities in the Andean region of Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia, the image brings to mind the mambeo, the chewing of coca, the sacred leaf that “satiates hunger, gives renewed vigor to those who are tired, and makes the unhappy forget their sorrows,” as the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega wrote in 1607. In this practice, coca is consumed along with lime (obtained from ground shells or ashes), which releases the active alkaloid present in the leaves, and the combination acts as a mild stimulant that allows its consumer to work long hours in high altitudes without eating. Besides providing stamina and nutrition, mambeo is a social activity for many indigenous cultures and can mark the transition to adulthood or an encounter with the gods.

Ethno-botanist Wade Davis explained the mythology behind the process in his groundbreaking book One River:

A profoundly religious people, the Kogi and Ika draw their strength from the Great Mother, a goddess of fertility whose sons and daughters formed a pantheon of lesser gods who founded the ancient lineages of the Indians. To this day the Great Mother dwells at the heart of the world in the snow fields and glaciers of high Sierra, the destination of the dead, and the source of the rivers and streams that bring life to the fields of the living. Water is the Great Mother’s blood, just as the stones are the tears of the ancestors. In a sacred landscape in which every plant is a manifestation of the divine, the chewing of hayo, a variety of coca found only in the mountains of Colombia, represents the most profound expression of culture. Distance in the mountains is not measured in miles but in coca chews. When men meet, they do not shake hands, they exchange leaves. Their societal ideal is to abstain from sex, eating, and sleeping while staying up all night, chewing hayo and chanting the names of the ancestors.[1]

The interpretation of this video as the mambeo would seem heavy-handed except that Herrán dedicated more than half a decade (1997–2003) to Papaver somniferum, a series that included videos, photographs, and installations that delved deeply into the social, political, and economic implications of the poppy plantations in Colombia. Papaver somniferum (the scientific name of the plant used to obtain opium and heroin) included several subseries, each dedicated to an aspect of the problem: the plantations, the flower and its bulb, altered states of consciousness, and the trafficking, surveillance, and eradication of the plant. Herrán’s continuing investigation of the social effects of the drug trade inevitably frames his earlier pieces and gives Untitled (1993) an interesting context.

[1] Wade Davis, One River: Explorations and Discoveries in the Amazon Rain Forest (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), 21.

El agua que tocas es la última que ha pasado y la primera que viene (The water that you touch is the last of what has passed and the first of that which comes) is a video installation by Nicolás Consuegra. The long title of this work, a line often attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, may strike us as something of a verbal puzzle, as it simultaneously confuses us and invites us to pause and consider its meaning. If we take the time to carefully analyze its parts, we will see that it focuses specifically on the paradoxical nature of the present, that volatile confluence of the past (what has passed) and the future (that which comes). The river referred to in the title is the river of time. Consuegra posits yet another version of Heraclitus’s famous aphorism: No man ever steps in the same river twice, which introduced philosophy to the subtleties of continuity and time. Indeed, continuity and time have never failed to perplex humanity with their paradoxes, from Zeno of Elea to Einstein and beyond.

The work itself takes the form of a paradox: various monitors project a succession of fixed perspectives, with a river that runs continuously from right to left, through the middle of each screen, where the horizon line would typically be. Shot in very similar light conditions, at different locations in the port of Honda on the Magdalena River, these moving photographs appear linked, creating the illusion of a single flowing image. Even if we are aware that what we see on one screen does not continue onto the next, we are deceived by the hypnotic flow of the river, and we cannot seem to escape the illusion of a single body of water. The water that flows out of one screen seems to be the same as that which enters the next.

This work could have been created along any river and at any port. It was, however, filmed in a forgotten port town, Honda, tied to the destiny of the Magdalena, a river that once was the main artery of the country but was then left to oblivion. It is the main river of a country condemned to sink, time and time again, into violence and despair. In Honda, nothing ever happens, nothing changes, and life stretches out as an eternal morass. Opportunities do not come, and oblivion takes the form of tedium and disillusion. City and river, both trapped in inertia, witness the passage of time without any promise of change, or of hope.

With this work, Consuegra proposes yet another ingenious game in his career as artist/illusionist. In an earlier piece he set various brain-teasing phrases into spiraling motion echoing Duchamp’s Anémic Cinéma; on another occasion, he reconstructed a room to replicate a photograph of it; and during his sojourn in the United States, he altered a series of “Exit” signs to read as “Exile.” For a group exhibition in Bogotá, which included the Magdalena River installation, he augmented the puzzle with an additional work: a large mirror, set at floor level, with a series of drinking glasses cut in half lengthwise, and affixed to the mirror. In the mirror’s reflection, the glasses appeared to be whole. The piece was titled, Nadie sabe de la sed con que otro bebe (No one knows the thirst with which another drinks).

All of Consuegra’s works share a sense of humor tempered by intellectual rigor, cynicism, and intelligence. Details are painstakingly rendered, and each piece is assembled with the utmost precision and control. In this game of mosaics with the Magdalena River, in which any of the pieces can be arranged in any order, we are witnesses to time disturbed. Despite our anticipation, nothing actually happens, and the steady flow of the river does not, in fact, guarantee anything, even the flow of time itself.

Translated by David Auerbach.

Installation view, Jorge Lizarazo, Nicolás Consuegra, and Carol Young. Bruce White, photographer.

Carol Young’s Memoria (Memory) consists of a long and somewhat dense series of thin ceramic sheets, each with its own unique folds and curves, like rocks, the veins in a cave, or a fissure in the land—each as individual as if created by nature. Yet all of the pieces fit together perfectly, unquestionably articulating an organic whole. Carefully mounted in an expansive installation, Memoria creates the impression of a fast-moving stream, with the curves evoking currents, and the arrangement of the pieces mimicking the movement of water rushing among stones.

This installation was part of the project Memoria y taxonomías del vacío (Memory and taxonomies of the void), which was short-listed for the 2011 Luis Caballero Award, Bogotá’s most competitive contemporary-arts prize. In the concurrent exhibition, viewers were invited to read the work in the context of an archive. Mónica Bonilla Young described the work for the exhibition:

Carol Young creates an image that it’s possible to associate with an ancient library, its innumerable pages and parchments, all rolled up and piled one on top of the other, archived and stored in a high-up niche, within some repository. They seem to contain evidence of times past, a collection of unknown, arcane information that calls out to be classified, reviewed, and studied.[1]

Memoria certainly allows for a wide range of interpretations and brings together multiple avenues of research. Young’s oeuvre includes an extensive portfolio of works devoted specifically to the manipulation of ceramic sheets, works that can be divided into three distinct types based on their sources of inspiration: paving stones, sheets of paper, and pieces of fabric. In the first type, there is an emphasis on the texture of the clay, on the materiality of the piece, and on its fissured, uneven edges. In the latter two types, the focus is on rendering the clay as thin as possible, simulating the folds of cloth or paper. To enhance the impression of paper, various kinds of inscpriptions are written into the clay. In exhibitions, the artist has two methods for presenting the works: they are either isolated, to heighten the individual traits, folds, and textures, or placed within the broader context of a large installation, where the pieces are mounted or grouped in specific ways, sometimes evoking a musical composition.

It is interesting to contrast Young’s work in ceramic sheets with her previous, parallel projects involving ceramic vases. In the 1980s and 1990s, she focused painstakingly on these paradigmatic ceramic objects, exploring virtually every possible form they could take. In particular, she experimented with thinning the clay, which resulted in ever more fragile pieces, while also highlighting their defining hollowness. She also played with their individual and collective appearances, particularly in her solo exhibition Agua (Water; Centro Colombo Americano, 1995), which presented a vast quantity of vases, each with a circular base. When viewed from various angles, the accumulation of hundreds of ridged circles looked like raindrops falling on a lake. Thus, through the medium of ceramics, Young managed to convey the profound relationship between water and the vessel traditionally used to carry it.

As with Agua, Memoria represents a pivotal point in Young’s work; the curved forms and jagged edges are the result of a long process of experimentation with the surface of ceramic sheets. Freed from function or the necessity to represent, ceramics become radically expressive and poetic. Piled up, repeated, the sheets configure a new whole: a massive chaotic archive, which is also a river, with a very particular memory, where everything is tangled up but also individually preserved.

Translated by David Auerbach.

Installation view, Jorge Lizarazo, Nicolás Consuegra, and Carol Young. Bruce White, photographer.

[1] See www.fotografiacolombiana.com/proyecto-nominado-al-vi-premio-luis-caballero/.

Jorge Lizarazo founded the textile workshop Hechizoo in 2000, and over the last fourteen years, he and his team of skilled colleagues (many of them trained by Lizarazo) have developed a truly innovative body of work with a deft mix of traditional and contemporary cultural references, materials, and techniques. The textiles they create mix natural fibers such as jute, raw silk, linen, and wool with materials seldom found in domestic textiles such as fishing line, copper or steel wire, twine, wrapping ribbon, glass rods, and twigs. In addition to working with more rarified materials, however, they also often “just take the same fibers available in the market and weave them differently,” as Lizarazo puts it. For Hechizoo, it’s a question of understanding and expanding the possibilities of textiles rather than merely taking advantage of the myriad new materials and techniques available through technology and the global market.

Although the fabrics that Hechizoo produces can all be used—as rugs, curtains, room dividers, upholstery, etc.—some are so structured as to have a sculptural presence, straddling the fields of craft, design, and contemporary sculpture.

In recent years, Lizarazo has been working with indigenous communities in the south of Colombia, in the state of Putumayo, a territory with great biological and cultural diversity. One such collaboration linked Lizarazo with the Inga people, an indigenous culture known for their intricate and colorful geometric patterns rendered with glass beads, usually for small-scale works such as jewelry. On one of his travels to the area, Lizarazo was able to acquire a canoe formerly used to transport coca leaves on the Putumayo River. The community was willing to sell the canoe to Lizarazo but was unaccustomed to treating their tools as commodities. They felt the need to regain their dignity after engaging in this kind of commercial activity and decided to give the boat a final “farewell” in the form of a “garment.” Thus an Inga family of eight came to the Hechizoo studio in 2013, where they stayed for almost half a year while painstakingly covering the outside surface of the boat with glass beads, expanding on their traditional patterns as they worked on a surface that was both familiar and, considering the task at hand, quite strange. The layers of traditional patterns covering the canoe correspond to specific images in the indigenous cosmogony: water, sky, and animals. “This canoe represents our environment, our traditions and our work: what we are,” said one of the proud craftsmen after they had finished this incredibly time-consuming work. This is the sense of dignity and pride that Lizarazo wants his pieces to convey.

Installation view, Jorge Lizarazo, Nicolás Consuegra, and Carol Young. Bruce White, photographer.

My initial inspiration for the design came after looking at an implement for removing the used tea leaves in Japanese tea ceremonies, which consisted of nothing but a piece of “stripped” bamboo. I thought of transferring this technique to the bottle, with a weft and warp in plastic and natural fibers. By combining a global object like the PET bottle and a global craft like weaving, a fruitful encounter between design and handicrafts was created. —Alvaro Catalán[1]

The PET Lamp project is an interesting example of how a product can appear in a designer’s mind simply by fusing two very different concepts that present themselves simultaneously. In this case, the challenge was two-fold: to devise a project that would recycle the PET (Polyethylene terephthalate) plastic bottles that pollute the world’s rivers and oceans, on the one hand, and to create an attractive, contemporary product that enlisted the talents of Colombian artisanal communities, on the other. The result, a series of unique ceiling lamps, represents the beautiful textiles woven in the Cauca region of Colombia and succeeds in finding a niche market that generates revenue for these communities, which presently face considerable economic and social problems.

In helping to create the PET Lamp project, the Cauca communities of Guambianos and Eperara Siadipara were able to share both their knowledge of traditional textile production and their distinctive use of color and pattern, resulting in original products that were colorful and festive. The project symbiotically combined contemporary design strategies with age-old, traditional practices. The proposal also included a very original approach to intellectual property rights. Inspired by the Copyleft model— common in the software-production world—designer Catalán de Ocón gave the artisans license to reproduce the lamps for their own use, while he creates elegantly designed PET Lamp installations in his studio for the international market. These beautiful, diverse installations can include as many as ninety-nine lamps, with no detail overlooked.

PET Lamps, in their coloring and variations, differ fundamentally from Catalán’s other lighting designs, which are defined by their minimalism. However, if we look more closely at his other lighting, we can see a sort of “philosopher of design” emerge, one who is primarily interested in the basic elements of each object and its function and seeks to bring out those elements in a way that explains the purpose of the object’s design. Two projects in particular demonstrate this aspect of his approach. One is the Cornucopia model, which includes only the most rudimentary components of a lamp, namely a bulb, electrical contacts, and a mirror to reflect light and control the way it is directed in a given space. The other is Candil, an electric bulb set in a wood and metal base, which generates a very soft and intimate light, reminiscent of a candle. When devising the handmade shades for the PET Lamp project, the designer drew upon his minimalist savvy—the plastic bottles provide an underlying structure as well as the warp, allowing the expert weavers endless possibilities to use their own traditional skills to create a range of woven designs by varying the weft fibers.

Indeed, Catalan “realized the project would work when [he] saw people going round the streets looking for bottles of the right color, shape, and condition for what they had in mind.”[2]

Translated by David Auerbach.

Installation view, Álvaro Catalán de Ocón, Lucy Salamanca, and Jorge Lizarazo. Bruce White, photographer.

Lucy Salamanca studied industrial design in Colombia and Italy and indeed for many years her work consisted of designing objects for mass production, collaborating with the likes of Paolo Orlandini, Aldo Cibic, and Ambrogio Rossari before founding her own studio in Milan: Zigurat Design Group. In 1991, she established Salamanca Design & Co. in Bologna, which operates both as a consultancy focusing on sustainable and fair-trade design for Asia and Latin America and as a design studio with an impressive catalog of products.

The Out of Balance collection of stools was conceived after several workshops Salamanca conducted in Curití, a small town in the Colombian northeast known for its use of fique, a natural fiber harvested from a plant native to Andean regions of Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. Over the past ten years she collaborated with Ecofibras, a cooperative project founded by the people of Curití in 1995 to market their goods, familiarizing herself with the local fibers and traditional techniques used to work with them. She has encouraged the group to branch out from its focus on bags and rugs to more innovative uses of their materials, including the production of furniture. The discovery of new possibilities for fique in Curití has been combined in Out of Balance with Salamanca’s similar work with another community in Colombia on the processing of guadua, a local variety of bamboo. Salamanca has stressed that the viability of her work over the years with Ecofibras depends in part on its willingness to encourage the employment of women, as many of them are heads of families. However, the production of the Out of Balance collection also required the physical strength of many male artisans to build the guadua structures and to weave their fiber coverings.

For Out of Balance, Salamanca has coordinated the design of the stools and chose the color of the fibers used, though at each step along the way, the artisans have worked to improve the original prototypes. Together, the designer and the craftsmen associated with Ecofibras have worked in dialogue to develop the production techniques and to reach an improved final product.

Installation view, Álvaro Catalán de Ocón, Lucy Salamanca, and Jorge Lizarazo. Bruce White, photographer.

The chairs produced by Marcelo Villegas are surprising not only for their expressionist qualities but also for their extremely simple and modern structural refinement. Instead of molding wood or metal to a specific shape, Villegas uses the natural curves in guadua bamboo, selecting perfect sections with which to build his powerful creations. The guadua root surfaces, which are coarse and full of texture, evoke the wrinkled hides of certain animals, so that each chair emits the sense of a living being with an imposing presence.

Villegas’s studio is in the department of Caldas, near the Cauca River, a region traditionally devoted to coffee production. As Villegas notes in the introduction to his book New Bamboo, in which various examples of guadua’s tremendous potential are presented, “Colombia’s coffee-growing areas were able to develop because of the presence of guadua, which was used in the construction of houses, bridges, fences, aqueducts, coffee-processing plants, and an endless list of other uses that were vital for the region’s progress. When settlers first arrived in the traditional coffee-growing areas in Caldas, Valle del Risaralda, and Valle del Cauca, in the vicinity of Pereira y Cartago, guadua was, in fact, the predominant species. It was later largely displaced by coffee plantations.We are now beginning to see reforestation of this species.”[1]

Villegas has been a champion in the campaign to reestablish guadua as a major source for building and design materials. He explains what makes guadua particularly suited for industry: “Guadua grows quickly and does not require much care. It’s also excellent for protecting and improving soil quality, since its root system serves to secure the soil, thus making it an irreplaceable species to protect against erosion. Guadua is a superb material because of its structural properties; it’s good for building, and it’s very light and highly resistant, while also being easy to cut and transport.”[2]

Along with the architect Simón Vélez, Villegas has created structural wonders that have gained renown in Colombia and abroad. Using an ingenious system for fastening together guadua poles, Vélez was able to create an almost infinite number of architectural forms, which he has used in a broad range of projects. Villegas joined the construction team for the Zeri Pavilion designed by Vélez for Expo 2000 in Hannover, Germany. The project tested the skill of the builders and the architect in a bold design that also showcased the enormous adaptability of the material. Since there were no building regulations in Germany applicable to bamboo, the project was first tested on a scale model built in Colombia, which still stands today in the city of Manizales—a testimony to the potential of this material.

Viewers are generally struck by the sheer visual impact of Villegas’s furniture. By working closely with the material, the artist has been able to make use of both the imposing texture of the bamboo and the great sculptural potential of its undulating curves. Villegas has proven his considerable talents as a sculptor and a connoisseur of materials, as can be seen in the furniture he has fashioned from the trunks and roots of towering trees. His furniture demonstrates an artist’s understanding of his country and its extensive natural resources. It also reveals his sharp eye for uncovering potentially complex forms, his ingenuity in creating sumptuous yet utilitarian objects, and his skill as a builder to utilize the full potential of natural materials.

Translated by David Auerbach

Installation view, Clemencia Echeverri and Marcelo Villegas. Bruce White, photographer.

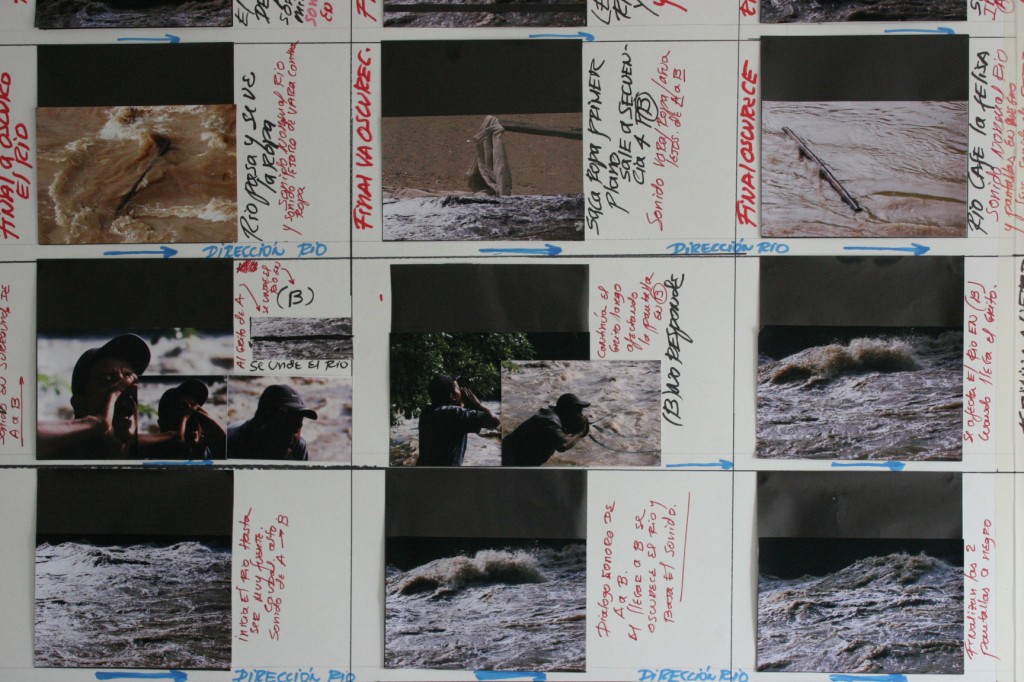

Clemencia Echeverri’s video installation Treno, with its projections on two opposite walls, not only immerses the viewer but forces him or her to turn around periodically in order to follow the dialogue between the images. The installation’s title is an archaic Spanish word that means funeral chant, from the Greek thrênos (lament). In ancient Greece, the thrênos was intoned when the dead body for some reason could not be found, and often entailed philosophical reflections on human destiny. The idea of a funeral chant for an absent body is at the origins of Echeverri’s installation, which references the innumerable bodies that are routinely thrown into Colombian rivers, where they disappear, foreclosing any possibility for the victims’ relatives to achieve closure. The casualties of a war that has lasted for half a century are innumerable, and thus the river has become, in many respects, a mass grave.

The video was shot on opposing banks of the Cauca River, a tumultuous body of water that runs parallel to the Pacific coast in Colombia and that eventually becomes a tributary of the Magdalena. This region has historically been, and still is, the site for violent confrontations. In Echeverri’s installation, the images of the roaring water are interspersed with shots of a man fishing out garments from the river with the aid of a pole. Periodically, a voice shouts out to the river, without any answer.

Echeverri has signaled that since Treno shows the opposing banks, it positions the viewer inside the river, as it were, and thus allegorically within the conflict:

Some rivers in Colombia have been, in their silent course, witnesses to a history that we reiterate tirelessly: an endless flow of all that we attempt to redress or amend. In Treno, a video installation developed on the banks of the Cauca River (in the environs of the Caldas and Antioquia Provinces) with local people, I put on an event whereby the moving image and sound bring into focus a time that the place itself keeps silent. Notwithstanding its apparent nature as a scenic viewpoint, a resting place, a natural wonder, the river carries unheard and errant voices; the juxtaposed experiences of a country that proposes and attempts its reconstruction at every step, while it is dragged down by a history that is tied to horror. I create a dialogue by way of two confronting projections that highlight discord and disintegration as constants that hamper the construction and that point to the void instead: an unanswered plea that speaks, indeed, of hopelessness.[1]

Installation view, Clemencia Echeverri and Marcelo Villegas. Bruce White, photographer.

[1] Clemencia Echeverri, Clemencia Echeverri: Sin respuesta / Unanswered (Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Dirección Nacional de Divulgación Cultural and Villegas Editores, 2009), 53–54.

When I was about six years old, I began finding out about things and hearing about the “centrales” (the people who knew). I would go anywhere there was conversation. During that time, when I was still a kid, I would listen carefully to my grandfather David (he was called “Ganaacqi” in the Muinane language). He was somewhere in his sixties, and he knew a lot of things, and he taught me the names of the trees and how they could be used and cared for. All the knowledge I have, I got from him. Later on, in my own community, I was called a “teacher.” It was up to me to adapt ideas so that others could understand and learn. Since I also knew stories, and history, and different ways of speaking, and I could also make connections between one thing and another, people would listen to me and they looked up to me as a wise man. Then the researchers from Tropenbos came, and they chose me to be a teacher to the researchers. So I had to teach them the names of the trees, the medicinal and non-medicinal plants, and the soil types, their uses, their life cycles, and their needs.

—Abel Rodríguez, interviewed by curator Oscar Roldán for the Salón Nacional de Artistas, 2013

Abel Rodríguez’s series, Ciclo anual del bosque de la vega (Seasonal changes in the flooded rainforest), has a story worthy of the complexity of its creator. Thought of as illustrations with an informative purpose, these colorful yet dense works of art not only illuminate their subject, the rainforest, but also retain some of its mystery. The drawings by Rodríguez, a member of the Nonuya indigenous people from the Araracuara region constitute just a small part of a larger venture—consisting of numerous books, videos, and other drawing projects—undertaken with Tropenbos International Colombia, an organization devoted to defending biodiversity on the grounds that ancient living cultures often possess knowledge not yet grasped by modern science.

It is difficult to come into contact with Rodríguez’s drawings, regardless of your background or interests, and not be surprised by what you discover in these awe-inspiring representations of seasonal change along the riverbanks in the tropical rainforest. In each drawing, you experience the power of synthesis: only a quick look grabs you, and if you take your time, you begin to discover the thousands of details hidden among the branches and understand the importance of presenting so many elements, and their interconnected relationships, in a single image. As a series, the works also express the mystery of continuity: the variations from drawing to drawing (from month to month) are so subtle that only by viewing them side by side do we appreciate their differences and understand the ecological phenomena that they capture and convey.

Rodríguez supplemented his cultural knowledge with resources that Tropenbos helped him acquire in Bogotá: the Chinese ink, tempera, and watercolor that allowed him to feel comfortable transferring the images in his mind onto paper. His drawings are done entirely by memory, built on knowledge acquired over many years that in turn reflect the wisdom of generations.

Rodríguez’s drawings, together with the extensive intercultural discussions that flow into and out of them, provide an exemplary model for Colombia, where relations between cultures have been notoriously difficult and indigenous peoples have repeatedly been victims of exploitation, violence, and segregation. That he and the project are now receiving recognition from academic, environmental, and arts-related institutions is only just—a fitting tribute for a remarkable individual and a special and inspirational case of intercultural dialogue and informational exchange.

Translated by David Auerbach.

Installation view, Alberto Baraya and Abel Rodríguez. Bruce White, photographer.

Tangrama is both an artists’ collective and a graphic design studio. As its projects move freely from museum to print shop to the street and back again, they reveal the porous boundary between contemporary art and design. The collective’s members’ work as artists centers on interventions and installations, printed materials, and poster designs, with a specific emphasis on the language of architecture and the dynamics of public space. As designers, they focus on graphic design for art institutions—including catalogues, posters, websites, brochures, guides, and maps—as well as exhibition design, with a heightened focus on graphic identity and the careful treatment of paper and other materials, regardless of format. Tangrama’s members—Mónica Páez, Margarita García, and Nicolás Consuegra—bring their own respective conceptual approaches, as befits art-school graduates, yet they share a core interest in visual grammar. Their artworks express the same graphic skill and refinement that they have developed as design professionals while their commissions for museums and other institutions demonstrate their conceptual acuity, which infiltrates all of their exhibition and publication graphics and designs.

The name Tangrama comes from the popular Chinese puzzle, tangram, in which a very limited number of pieces (seven) can generate a seemingly endless quantity of figures. The name, which they chose many years ago, also symbolizes many of the collective’s core principles and interests: graphic language, patterns, games, puzzles, and riddles. The collective’s working strategies reveal various paradoxical elements that seem drawn from the world of game playing, including elements of problem solving, hiding and seeking, fooling the eye, and making hidden structures explicit. One of their earlier works, a unique, graphic, street intervention, was particularly representative of these techniques and ambitions. They created a series of posters, each reproducing a distinctive pattern of brick, and then plastered the posters on various brick walls, near “Prohibido Pegar Carteles” (Post No Bills) notices. Passersby were confronted by a wall, covered in posters that obscured other posters by mimicking a wall, challenging them with an apparent contradiction. In the end, their “bricks” would also be covered by new posters.

Given their conceptual interest in patterns and their demonstrated design talent, the collective was invited to participate in Waterweavers. They were given the challenge of revisiting and elaborating on the graphic elements David Consuegra identified in pre-Hispanic objects produced by the Muisca and Tolima cultures, as they appear in the book Ornamentación calada en la orfebrería indígena precolombina (Decorative Openwork in Pre-Columbian Indigenous Metalwork).

Inspired by themes of the river and of weaving, the members of Tangrama recognized that the pre-Hispanic patterns Consuegra identified could be reproduced in an infinite, linear fashion. For this exhibition they developed an interactive digital application that could set the patterns into virtually limitless motion, thus transforming each pattern into a river (water), while also allowing users to superimpose layer upon layer (weavers).

This project is analogous to what Consuegra achieved in his book. By extracting an element from each indigenous artwork, he demonstrated the graphic wealth of pre-Hispanic cultures. Similarly, by setting these elements into motion, and by triggering a virtually endless series of reproductions and superimpositions, Tangrama exposes the true potential of these graphic units as patterns. The project is as simple and powerful as the tangram game, in which the broken pieces of a square can generate a universe of forms solely through the art of combination.

Tangrama’s work allows visitors to the exhibition to experience the rhythmic motifs Consuegra first perceived in these pre-Hispanic objects. The mechanism that they have created, aside from employing a digital application (which is nonetheless engaging, given the animation it generates), provides a new strategy for creating imagery—a vocubulary that can be used to produce a great variety of printed images, including posters, fabric borders, wallpaper designs, etc. The results can be seen in the pages of this book, which were also created from Tangrama’s game-like strategy.

Translated by David Auerbach.

Installation view, David Consuegra, Tangrama, and Abel Rodríguez. Bruce White, photographer.

In 1968 David Consuegra published the book, Ornamentación calada en la orfebrería indígena precolombina (Decorative Openwork in Pre-Columbian Indigenous Metalwork), to commemorate the opening of the newly constructed modernist building for Colombia’s most visited museum, and one essential to its national identity, the Museo del Oro (Gold Museum) in Bogotá. The book was a celebration of Colombia’s most important collection of pre-Hispanic precious metalwork, emphasizing connections between contemporary abstraction and the works produced by local indigenous cultures. Indeed, the common goal of both the museum and designer was to create powerful, symbolic, and historically resonant visual elements that could be used as icons to formulate a modern Colombian identity freed from persistent colonial constraints.

Ornamentación features various pre-Hispanic gold pieces, created by the Muisca and Tolima cultures, meticulously photographed in black and white. Consuegra isolated individual visual motifs from the artworks and then developed them as patterns. Each pattern was drawn and silkscreened in a range of colors, creating linear motifs (either horizontal or vertical) that convey a sense of rhythm and movement. The result is a visual study that is also highly original in its approach to formal analysis, with existing ancient motifs being reworked to create new designs.

Consuegra studied graphic design at Yale University, under the tutelage of Paul Rand, among other renowned instructors. After returning to his homeland, he soon became a central figure in the establishment of graphic design as a separate discipline in Colombia, both by creating academic programs at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia and Universidad de Bogotá Jorge Tadeo Lozano, and as an artist, devoting himself specifically to the design of logos, symbols, posters, and books.

Many of the logos he designed are still in use today, while others are imprinted in the memories of most Colombians, such as those for Inravisión and Artesanías de Colombia. One of his most significant creations was the logo for Bogotá’s Museo de Arte Moderno (MAM). For this logo he proposed various geometric patterns based on his own penchant for openwork ornamentation. For MAM Consuegra also created a variety of provocative designs that exploited the virtually limitless potential of any given graphic pattern. His poster designs for various MAM solo exhibitions exercised considerable liberty in reinterpreting the work of each exhibited artist through his own illustrations and typography (another field that he pioneered in Colombia) while capturing their stylistic essence.

The creation of a new Colombian identity—one that was patently modern but with local roots—became a professional passion that he shared with many of his artist, designer, and architect contemporaries. The results are best exemplified by his work for MAM, its exhibitions, and its unique graphic identity.

It is in his books, however, that Consuegra’s talents as a graphic designer are perhaps best expressed and where his tireless spirit as a scholar and original artist are most visible. Projects such as On Trademarks, Graphica et Lettera, En busca del cuadrado (In Search of the Square), American Type, and, of course, Ornamentación demonstrate Consuegra’s uniquely modern proclivity for schematically organizing a universe of design elements. These works also underscore the intellectual rigor—possibly the best term to describe all his work—with which he isolated essential elements and communicated them through a highly effective and astutely insightful graphic language.

Translated by David Auerbach.

Installation view, David Consuegra, Tangrama, and Abel Rodríguez. Bruce White, photographer.

Trained as an industrial designer and self-defined as a sculptor, Ceci Arango has been creating objects for more than two decades. Early on, she determined that in a country without a strong industrial base or culture of design, it would be very difficult to produce prototypes for mass production, so she opted for a radically different route, choosing instead to conceive of functional pieces that could be produced in small batches, following the logic of craft production. This decision proved to be wise, as in recent years there has been a renewed interest in the handmade object. Craft dignifies the individual producer, makes rational use of local materials and traditions, and resists the fast pace of industrial output, where products tend to be consumed and discarded as swiftly as they are manufactured.

Arango often works with craftsmen and craftswomen, taking advantage of given traditional forms or modes of production and changing them slightly to better suit the requirements of her designs. The Corocora stool, designed in 1993 and in production ever since, takes its name from the scarlet ibis, a bird commonly found in Colombia. The long legs and colorful seat of the stool brings to mind the ibis when seen from a distance. Arango acquainted herself with a spiral weaving process typical of several communities in Colombia, in which a core of esparto fibers is wrapped in fine fique thread and becomes a tubular form that can be stitched together following an outward spiral. The process lends itself to flat forms (and indeed is often used in making placemats), but it can be given volume to create vases, bowls, or trays by altering the surface until it becomes concave or convex.

Arango saw the possibilities of this process and designed a very simple stool that has become an icon of contemporary Colombian design. The seat is done in spiral weaving, and, as the weave curves around a wooden core, it creates a base where the legs can be attached. The slender tripod-like structure that constitutes the legs is made with macana palm, a very strong wood whose weather-resistant properties make it a favorite for balconies in rural Colombia. The legs are joined at the center with copper wire so that they can fold into a bundle for shipping or storage. Arango has worked with a group of craftsmen in the town of Guacamayas (which is famous for its basket weaving) to fabricate this design, thereby providing sustenance for the community for over twenty years.

Installation view, Monika Bravo and Ceci Arango. Juan Luque, photographer.

Monika Bravo’s URUMU [WEAVING_TIME] is a video installation that rapidly envelops the viewer in a textile. Intermittently, across three walls (the entirety of the viewer’s field of perception), “threads” shoot up and down creating a virtual warp. At the same time and with the same irregular rhythm, weft “threads” move left and right, creating a weave. The resulting graphic “woven” image appears to constitute a text written in an unknown foreign language. As the weaving process continues, the graphic image of the pattern slowly fades into a video that at the end reveals a view of an undetermined location, seemingly devoid of the traces of human beings.

The meaning of the virtual weavings will vary depending on the viewer. For people who grew up outside of Colombia, they might seem like abstract patterns, possibly recalling the graphic motifs of an indigenous South American culture. For Colombians, they will evoke mochilas arhuacas, the Arhuaco bags which are ubiquitous throughout the country and are also a popular tourist souvenir. For the Arhuaco (Ika) people who inhabit the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta region, however, the motifs have a very specific meaning, each element symbolizing a fundamental idea within their culture. As one member of this indigenous community has stated, “The universe that shelters us is a spiral and dwells in the bottom of my backpack. The threads of my knowledge come from before, and have been intertwining since I was a girl.”[1] In the area in which they live, which they share with the Wiwa and Kogi peoples, a stunning mountain range that forms a distinct geographic border adjacent to the Caribbean Sea, textiles are both practical and symbolically significant. The communities of the Sierra Nevada, despite their tense and tenuous dialogue with the modern world, have been able to preserve ancient rituals and traditions that rely on other ways of relating to nature.